Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

Dr. Michael Weiner is the lead investigator on a study examining possible links between TBI or PTSD in dementia in Vietnam Veterans. (Photo by Ed Caballero)

October 5, 2017

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

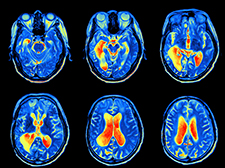

Dr. Michael Weiner's group at the San Francisco VA used MRI scans and other measures to investigate the link between traumatic brain injuries and Alzheimer's disease. (Photo ©iStock/alkesak)

The possibility that brain injuries are a precursor for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s is of keen interest to the medical community.

Many studies, in fact, have examined the potential ties between traumatic brain injury (TBI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia. Most of those studies have linked TBI, the signature injury from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s.

Now, a prominent VA neuroscientist, Dr. Michael Weiner, and his research team are questioning whether TBI elevates one’s chances of developing Alzheimer’s. They base their theory on two recent studies, one by Weiner’s group. In an analysis published in October 2017 in the journal Neurology, Weiner says these two “large, well-powered, and carefully conducted studies cast substantial doubt on the association between TBI exposure and AD outcomes, both overall and among males and carriers of the [APOE-e4] alleles.” The latter is known as a risk-factor gene because it substantially increases a person’s likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s.

“Perhaps these findings will be reassuring to our Veterans and others with a history of TBI,” says Weiner, who is with the San Francisco VA Health Care System. He says the rising media attention on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, another degenerative brain disease that is being found in many deceased football players, has contributed to a widespread belief that one TBI may cause problems such as Alzheimer’s. “The results from our two independent studies might relieve some of the anxiety,” he says.

"Perhaps these findings will be reassuring to our Veterans and others with a history of TBI."

While the scientists do strike an optimistic note regarding Alzheimer’s, they also warn that TBI may raise the long-term risk for other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, a chronic and progressive movement disorder.

Weiner is the lead investigator on one of the studies, which examines possible links between TBI or PTSD in dementia in Vietnam Veterans. The ongoing Department of Defense (DoD)-funded study is using VA medical records to document a history of TBI and established AD biomarkers to measure the development of Alzheimer’s, almost entirely in men. The researchers are investigating the extent to which a history of TBI increases the odds of developing cognitive impairments or changes in AD biomarkers. The biomarkers include structural brain changes seen on MRIs and amyloid deposition measured by PET scans. MRIs and PET scans are radiological imaging tests used to check for abnormalities in the brain.

Although Veterans who had a TBI had an increased sign of mild cognitive impairment, the results showed no effects of TBI history on AD biomarkers.

Amyloid plaques and tau tangles, which lead to cell death and tissue loss in the brain, are the two abnormalities that define Alzheimer’s. The deterioration of nerve cells in the brain in turn affects thoughts, memory, and language. The disease is one of the leading causes of death in the United States.

Weiner cautions that the results of the DoD-funded study are preliminary, noting that more work needs to be done to determine if TBI does lead to Alzheimer’s.

The DoD study is a spinoff of the Alzheimer’s disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), which is also led by Weiner. ADNI researchers are working to define the progression of AD by analyzing data such as MRI and PET images. The study, funded mainly by the National Institute on Aging and involving about 60 clinical sites across the U.S., has expedited research on the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s over the past decade.

The other study was led by Dr. Paul Crane, who specializes in research on Alzheimer’s and cognitive functioning at the University of Washington. He is a co-author of Weiner’s analytical paper.

In Crane’s study, self-reported information on TBI was collected when the participants, who had been unconscious for at least an hour immediately after an injury, were “cognitively intact.” The researchers investigated the late effects of this TBI in three large studies on brain aging and dementia that asked participants to donate their brains for research.

Nearly 1,600 participants underwent a brain autopsy over a 20-year period (1994 to 2014). The studies showed that a history of TBI with loss of consciousness was not linked to Alzheimer’s, dementia, or the neuropathologic features of AD. Instead, the TBI was associated with Lewy body disease, another common cause of dementia in the elderly, as well as Parkinson’s disease.

“Unlike some epidemiological studies, well-powered analyses did not find interactions between clinical or neuropathologic AD outcomes for TBI and the [APOE-e4] genotype or sex,” Weiner and his colleagues write. People who develop Alzheimer’s disease are more likely to have an APOE-e4 allele than people who do not develop the disease. The gene has been found in about 40 percent of all people with late-onset Alzheimer’s.

According to Weiner, the DoD-funded study and the Crane-led study avoid the limitations that have been in nearly all of the epidemiological studies examining links between TBI and Alzheimer’s. He explains that most of those studies have used the “self-report” approach to determine a history of TBI exposure.

“The collection of exposure data from people who are already cognitively impaired has obvious drawbacks in the reliability of the data,” he and his research team write. The other limitation is that most studies have relied on the clinical assessment of physicians, which is a very imperfect approach to diagnose AD, rather than on recently developed biomarkers or an examination of the nervous system, Weiner says.

Weiner acknowledges that his study and the Crane-led study have limitations, too. He says his paper includes a relatively small sample size, although his team is continuing to enroll participants. In the case of Crane’s study, the major conclusions come from autopsy findings.

“The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s pathology was not made in living subjects, as was the case in my study,” Weiner says. “It’s possible that there could be some sort of selection bias in the people who have volunteered for an autopsy. It’s also possible that the type of people who had autopsies are not representative of the general population.”

He adds: “These studies need replication, which is our major conclusion.”

To gain a more accurate picture, Weiner and his colleagues support further investigation to determine the relationship of TBI to cognitive decline in the elderly “in order to effectively address this serious public health problem,” they write.

“The association of TBI with Parkinson’s disease neuropathology suggests that TBI

exposure is not innocuous and is consistent with a recent large epidemiological study that found an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease following late-life TBI,” the researchers write. “Neuropathological outcomes appear to differ depending on the severity or frequency of the TBI.”

Weiner calls for a “very large epidemiologically sampled study of Veterans and civilians who have documented TBI,” according to hospital records or other strong documentation, not simply self-reported cases. He notes that the study would use advanced biomarker methods such as amyloid PET scans, tau PET scans, cerebral spinal fluid measurements of amyloid and tau proteins, MRIs, cognitive tests, and studies of the brain following an autopsy.

“This is not a closed issue,” he says. “I’m sure that this kind of study could be done well with only $100 million for the first five years. Our Veterans deserve it!”

He says he maintains an “open mind” on whether scientists will eventually find a definitive link between TBI or PTSD and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

“Our preliminary results, and the results of Crane et al, suggest that the thought of a link between TBI and Alzheimer’s may not be as strong as previously thought,” he says. “It might not exist at all.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates