Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

Dr. Eric Elbogen is a forensic psychologist at the Durham VAMC. His recent research has focused on returning Veterans' risk factors for criminal and violent behavior, homelessness, and other reintegration problems. (Photo by Linnie Skidmore)

September 13, 2013

By Mitch Mirkin

VA Research Communications

Earlier this year, when an Iraq Veteran who had been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder shot and killed Chris Kyle, a former Navy SEAL who wrote the autobiography American Sniper, a slew of news reports focused on the PTSD angle.

National Public Radio aired a story titled "Shooting of 'American Sniper' Raises Questions about PTSD Treatment." ABC News headlined its report, "Former Navy SEAL Chris Kyle's Killing Puts Spotlight on PTSD."

According to Eric Elbogen, PhD, the media—and people in general—often want to "explain acts of violence without going deep enough into the multiple causes. PTSD is related to violence, but so are lots of other factors."

"The PTSD diagnosis is relevant, but it's the tip of the iceberg. And people often stop there in terms of looking at why an incident may have happened."

Elbogen is a forensic psychologist who studies the link between mental health and criminal behavior, particularly violent crime. In recent years, much of his work has focused on returning Veterans.

The researcher, based at the Durham VA Medical Center and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Medicine, says one of his key messages is that PTSD is not the same for each Veteran. It's different from one person to the next. Some might have PTSD symptoms that, according to research, do predict violent behavior. Others might have a form of the disorder that is in no way linked to violence or aggression.

A related message Elbogen tries to convey is that "you have to go beyond PTSD."

"You have to consider the non-PTSD risk factors," he says. "These people may have served in a war, but they're also human beings, civilians. You have to look at factors such as younger age, a history of violence before the military, financial instability, lack of emotional support network, substance abuse. Some of these factors are stronger than PTSD as predictors of criminal behavior."

He acknowledges that some of the factors are intertwined in subtle ways, and there is much that even the experts don't fully understand. But they all have to be considered to "avoid a kneejerk reaction" to a complex problem, he asserts.

"The PTSD diagnosis is relevant," he says, "but it's the tip of the iceberg. And people often stop there in terms of looking at why an incident may have happened."

VA Researcher Named One of U.S.’ Top Female Scientists

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

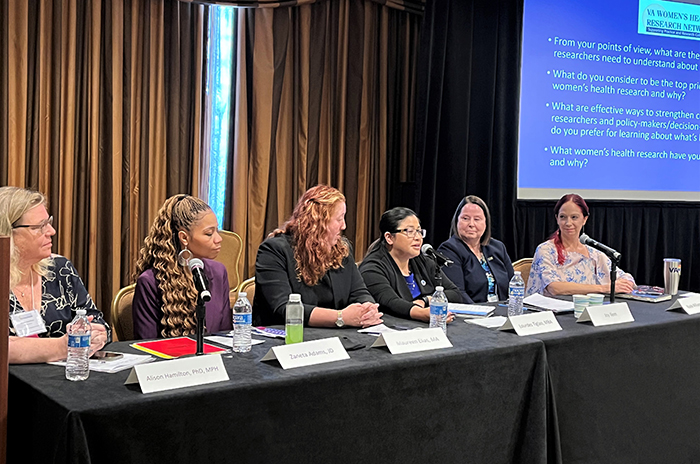

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

During a recent talk, Elbogen asked attendees to estimate what percentage of returning Veterans had been involved in some form of violent behavior in a one-year span. The guesses ranged from 5 to 80 percent. "The estimates were all over the map," says Elbogen.

He shared with the audience study findings from a representative sample of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans, VA and non-VA enrollees alike, from all branches of the military and all 50 states. Elbogen summarizes those results:

"We found that about 10 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans had reported severe violence—harming someone else, or inflicting potentially lethal harm—during a one-year period," says Elbogen. "In total, 25 percent reported some type of physical aggression toward others in that time frame."

Among those who had received a PTSD diagnosis, says Elbogen, the percentage of those who reported committing violence during the following year rose from 10 to 20 percent. However, notes Elbogen, "Among that 20 percent, there are those with a history of violence or criminal arrest before they joined the military. If you isolate only that group, the number jumps to 32 percent. But if you take them out, and look only at people with PTSD and without this prior history, the number goes down to 15 percent."

"It's tricky," he says. "It depends how you 'slice' the data. But that's what we know using this national data. That's the scope of the problem."

The bottom line, he says, is that "the majority of Veterans, with or without PTSD, did not report violence, aggression, or criminal behavior. At the same time, the data indicated that violence remains a serious problem for a subset of Veterans."

Elbogen says financial instability is an underappreciated risk factor for returning Veterans. He has conducted money-management workshops at the Durham VA Medical Center for the past six years, with funding from the Department of Education. "The Veterans love it," he says. "It's getting at everyday life, the decisions they make."

Poor money-management skills, not surprisingly, can put Veterans at risk for a host of problems, including homelessness, he notes. That point was borne out by a study of Elbogen's that will be published soon in the American Journal of Public Health. "The article should be an eye-opener for people," he says. "On the one hand, as my statistician likes to say, it's empirical data showing the glaringly obvious—that if you don't manage your money well, you can become homeless. On the other hand, no one I'm aware of has published this finding yet—for Veterans or civilians."

Elbogen says case managers who staff homelessness programs in VA often provide informal money management help for Veterans. But it's not required or formalized. "This is a potential opportunity for VA," says Elbogen.

The latest diagnostic guidelines group PTSD symptoms into four clusters:

Re-experiencing— These include, for example, flashbacks, bad dreams, and scary thoughts.

Hyperarousal —Jumpiness, irritability, and anger; sleep problems; reckless, aggressive, or destructive behavior.

Avoidance and numbing— Feeling emotionally numb; staying away from anything that might trigger traumatic memories.

Negative thoughts and mood or feelings —Depression or guilt; problems with concentration or memory; social withdrawal.

Until this year, the second category, hyperarousal, had not explicitly included the violence-related symptoms. Prior research by Elbogen and others had in fact revealed a strong link between violence and aggression and the other hyperarousal symptoms—especially irritability. One study found that Veterans with PTSD who were frequently irritable were twice as likely to get arrested, compared with others with PTSD but without that symptom.

Another more recent study by his group found that anger—part of hyperarousal—was related to family violence. The study also found, for the first time, that flashbacks—part of the "re-experiencing" cluster—were related to violence against strangers. Elbogen cautions, though, that the flashback linkage needs to be confirmed in further research.

Elbogen says it's important for researchers to continue to tease out the different PTSD symptoms and understand which are predictive of violence or other dangerous behaviors, and which are not. "A clinician seeing a Veteran wants to know, what are the things I need to be attuned to, to know if this Veteran is at risk."

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates