Office of Research & Development |

|

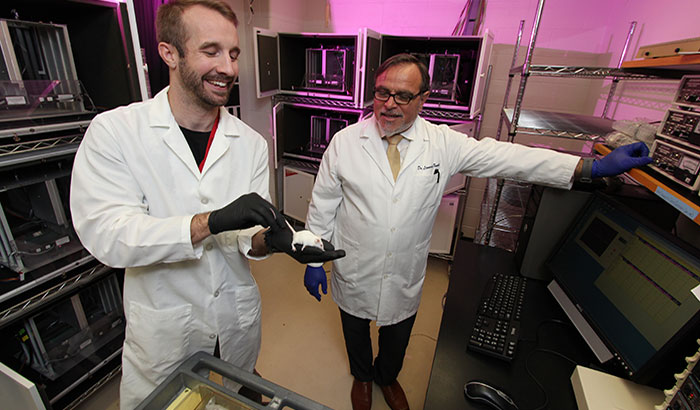

Dr. Leonardo Tonelli (right) and research assistant Brent Stewart are conducting mouse studies to learn about the role of the immune system in mental health. (Photo by Mitch Mirkin)

December 11, 2018

By Mitch Mirkin

VA Research Communications

"We now know the immune system and the brain have everything to do with each other."

If you cut your finger or stub your toe, or a virus enters your body, your immune system responds. A fierce army of white blood cells mounts an attack.

How about when emotional trauma or depression strikes? We may not think of the immune system as part of the healing process.

But that thinking is outdated. Just ask experts like Dr. Leonardo Tonelli, of the Baltimore VA Medical Center and the University of Maryland. A psychoneuroimmunologist, he studies the link between the nervous system—mainly the brain—and the immune system.

Tonelli believes the immune system may be a potent tool for treating depression and post-traumatic anxiety, or even full-blown PTSD, in Veterans. He is conducting experiments in mice that he hopes will spawn new therapies—such as rebuilding or reshaping a patient’s reservoir of T cells, which are subsets of white blood cells. The “T” is for the thymus gland, where the cells mature.

“Perhaps it will require a stepwise approach of getting rid of the ‘bad’ T cells and rebuilding the ‘good’ T-cell population,” speculates Tonelli.

One approach, he says, could be using a patient’s own stem cells to grow new T cells, and then injecting those into the body. A less invasive approach might be using a “super probiotic” to jump start a healthier T cell population.

“All these options are on the table,” Tonelli says.

VA Researcher Named One of U.S.’ Top Female Scientists

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

His newest VA-funded mouse study is a deep dive into how exactly stress affects the immune system—and whether manipulating T cells can alter behavior. If behavior can be normalized in mice, the hope is that the effect can one day be translated into humans.

The focus is on two types of T cells. One is CD4+ cells. They are known as “helper” cells because one of their main jobs is to send signals to activate other immune cells. The other is CD8+ killer cells, which earn their fearsome moniker because they knock off cancerous, infected, and other damaged cells.

Tonelli’s lab uses genetically altered fluorescent T cells. Their green glow allows them to be tracked microscopically as they migrate into different tissues—including the brain.

The team injects these cells into genetically engineered mice that lack T cells. This way, the researchers can carefully follow what the cells do and where they go.

Another phase of the work involves administering antibodies that neutralize CD4+ and CD8+ cells. The mice are then assessed for anxiety, despair, and startle response.

Mice can’t fill out questionnaires. So how can scientists test their symptoms? One way is a “social interaction box.” A mouse is placed into a two-compartment box, open at the top. In one of the compartments is another mouse, in a small enclosure. If the mouse being tested shows signs of trauma—analogous to PTSD— she will tend to avoid the other mouse. A mouse that is emotionally intact will be more social.

Yet another phase of the study involves blocking certain proteins in the immune system to tease out their role in T-cell-mediated inflammation.

Tonelli expects the results of these and other experiments to “provide proof of concept” that CD8+ T cells are the main culprit in the inflammation triggered by traumatic stress, and that “it is possible to reduce inflammation and improve emotional regulation by targeting these cells.”

He hopes the work will eventually benefit many patients, but especially those with military PTSD. His group is in the forefront of exploring the immune system as a potential healing resource for this population.

The concept is drawing increasing interest from experts in the biology of PTSD.

“The link between PTSD and chronic illness has been established but the potential role of immune system markers in mediating this association is only beginning to be examined,” wrote VA clinician-researchers Drs. Janine Flory and Rachel Yehuda in a special report in Psychiatric Times in April 2018.

Flory and Yehuda raised several intriguing questions that tie into Tonelli’s work:

In the same issue of Psychiatric Times Dr. Charles Raison, with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, offered further perspective on the topic. He wrote that his time in medical school in the 1980s was like the “dark ages,” with respect to understanding the brain-immune connection.

“We now know the immune system and the brain have everything to do with each other; really, they are best understood as part of one larger system with causal influences that move in both directions. Brain states that produce mental illness also tend to activate inflammation. And inflammation is equally capable of producing depression, anxiety, fatigue, and social withdrawal.”

He added that environmental insults—for example, toxic exposures—can hike inflammation and “likely increase the risk of mental illness through this mechanism.”

Tonelli shares that view. He points out that military PTSD may be different in its complexity than other forms of the disorder—for example, like that seen in cases of sexual or child abuse—because war can mean not only severe emotional trauma, but also bodily injury, exposure to extreme heat or cold, sleep deprivation, and other physical assaults on the human organism.

“We need to incorporate physical trauma to the pathophysiology of PTSD,” he says. “Getting hurt physically in any way is an important mechanistic process leading to PTSD in which the immune system and inflammation play crucial roles.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates