Office of Research & Development |

|

Patients with Parkinson's disease who undergo deep brain stimulation (DBS)—a treatment in which a pacemaker-like device sends pulses to electrodes implanted in the brain—can expect stable improvement in muscle symptoms for at least three years, according to a VA study published online June 20 in the journal Neurology. The trial is among the longest-term studies on the topic to date.

VA cares for at least 60,000 Veterans with Parkinson's disease, and it's estimated that around two percent—some 1,200—have undergone DBS, either at VA or non-VA facilities, according to lead study author Fran Weaver, PhD, of the Hines (Ill.) VA Medical Center and Loyola University.

The trial was done at several VA and university medical centers and supported by VA's Cooperative Studies Program and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health. The maker of the devices used in DBS, Medtronic Neurological, helped fund the research but did not play a role in designing the study or analyzing the results.

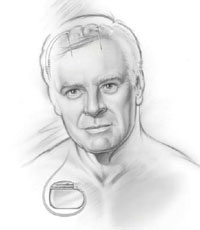

In DBS, surgeons place electrodes in the brain and run thin wires under the skin to a pacemaker-like device implanted near the collarbone. Electrical pulses from the battery-operated device jam the brain signals that cause muscle-related symptoms.

Thousands of Americans have seen successful results from the procedure since it was first introduced in the late 1990s. But questions have remained about which stimulation site in the brain yields better outcomes, and over how many years the gains persist.

Initial results from the VA study appeared in 2009 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Based on the six-month outcomes of 255 patients, the researchers concluded that DBS is riskier than carefully managed drug therapy—because of the possibility of surgery complications—but may hold significant benefits for those with Parkinson's who no longer respond well to medication alone.

A follow-up report in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010, based on two years of follow-up, showed that similar results could be obtained from either of the two brain sites targeted in DBS.

The latest report is based on three years of follow-up on 159 patients from the original group. It extends the previous findings: DBS produced marked improvements in motor (movement-related) function. The gains lasted over three years and did not differ by brain site.

Patients, on average, gained four to five hours a day free of troubling motor symptoms such as shaking, slowed movement, or stiffness. The effects were greatest at six months and leveled off slightly by three years.

The extra year of follow-up, however, revealed declines in other areas that had not been seen in the earlier analyses.

"Some early gains in quality of life and activities of daily living are gradually lost, and decline in neurocognitive function is seen over serial evaluations," wrote the authors.

The researchers said the losses most likely reflect the natural progression of the disease, and possibly the worsening or emergence of some symptoms that resist DBS and drugs.

Earlier research on the treatment had suggested better muscle control could be achieved by targeting the subthalamic nucleus (STN) rather than the globus pallidus interna (GPi)—two areas of the brain involved in movement. On the other hand, GPi stimulation was seen as posing less risk of side effects such as depression or impaired thinking.

On the whole, the VA-NIH trial has found both brain sites roughly equal for outcomes relating to movement. The investigators say the results may reflect the benefits of newer surgical techniques and care practices that were not in place when earlier studies of DBS were conducted in the early 2000s.

The latest analysis did find some cognitive declines in the STN group, whereas the GPi group actually improved somewhat, consistent with past findings.

For now, says Weaver, "Providers and patients should consider both motor and non-motor symptoms when choosing a surgical target for DBS." For example, a patient who is already showing signs of mental decline may be a better candidate for GPi stimulation.

The researchers plan to continue following the patients in the study for several more years. Weaver points out that a patient who is benefiting from DBS should be able to stay with the therapy his entire lifetime. As such, researchers want to "look longer to see what happens."