Office of Research & Development |

|

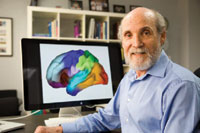

How do genes affect brain development and function? Scientists seeking clues may now have an edge thanks to a new "brain atlas" developed by VA researchers and colleagues. The research, described in the March 30 issue of Science, involves twins who served in the military during the Vietnam era.

More than 406 twins took part, in San Diego or Boston, as part of the larger Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging. The Veterans underwent MRI scans of their brains. Because of the twins' genetic similarity, the researchers were able to deduce what role genes play in forming the brain.

The study zeroed in on the cortex, the outer layer of the brain. Dense in "gray matter," this region is where higher-level thinking takes place.

"What we've done is create the first brain atlas based only on genetic data," says VA and University of California, San Diego, psychologist William Kremen, PhD, the study's lead investigator.

Traditional brain maps divide the brain into regions based on structure and function. As early as 1909, German scientist Korbinian Brodmann studied the different cells and tissues in animal and human brains and identified more than 50 distinct areas. Through decades of experimentation, scientists have learned more about each area's role.

Still absent from the picture, though, is knowledge of what role genes play. Kremen notes that scientists have lacked "understanding of the genetic underpinning of these regions. Do the same genes influence different regions, and is it the same for both sides of the brain? If two brain areas are functionally connected, does that mean they are influenced by the same gene? These are questions we don't have answers for yet in neuroscience."

The new study did not pinpoint the role of specific genes. However, it did yield a map of the brain divided into clusters, each of which appears to be affected by a distinct set of "genetic influences," says Kremen. Using a mathematical model, the researchers determined that 12 such clusters was the optimal breakdown. Each area is marked by a different color on their new brain atlas. Explains Kremen, "You could look at the atlas and say, for instance, that a lot of the same genetic influences are at play in the blue region, and those are different than the genetic influences in the yellow area."

Remarkably, says Kremen, the new atlas—based solely on genetic data—resembles traditional maps based on structure and function, even though his group used no such existing references as a starting point. They had no preconceived notions of what their new algorithm-driven atlas would look like. "This was an ‘agnostic,' purely statistical approach," comments Kremen.

How will the new atlas be used? One potential application, says Kremen, is genomics research. Neuroscientists are conducting many "genome-wide association studies" in which they collect DNA from study volunteers and try to piece together which gene variants predict certain brain conditions, such as posttraumatic stress, alcohol addiction, or Alzheimer's disease.

Using the genetic atlas, says Kremen, "Researchers may be more likely to pinpoint the genetic influences that underlie the various structures in the brain."

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging and involved researchers from several institutions, including VA, UCSD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Boston University, Harvard Medical School, and Massachusetts General Hospital. Lead author was Dr. Chi-Hua Chen, and co-senior author was Anders M. Dale, both of UCSD.

The study volunteers were from the Vietnam Twin Registry. The total registry contains data on some 7,000 middle-aged male twin pairs, all of whom served in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. Managed by VA's Seattle-based Epidemiologic Research and Information Center, the registry is among the largest twin registries in the nation, with members in all 50 states. While it was initially formed to help answer questions about the long-term health effects of service in Vietnam, the registry has become a resource for genetic and epidemiologic studies on a wide range of mental and physical health conditions.