Office of Research & Development |

|

Dr. Andrew Schally may not yet have found the fabled "cure for cancer," but he's come about as close as any biomedical researcher.

Nowadays, well into his 80s and having just marked his 50th anniversary as a VA lab researcher, the winner of the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is still hot on the trail of compounds he believes will revolutionize cancer treatment. And over his decades-long career, he has been credited with huge advances in a range of additional medical fields, such as gynecology, gastroenterology, and endocrinology.

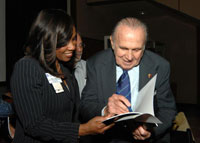

On Oct. 19, friends and colleagues of Schally gathered at the Miami VA Medical Center to commemorate his 50th anniversary conducting research within VA. The department presented Schally with a plaque recognizing his "extraordinary accomplishments over more than 50 years and [his] contributions to numerous medical breakthroughs and research advancements."

Born in Europe, Schally came to Canada, and later the U.S., after World War II. He joined VA in 1962 and set up a lab devoted to studying the brain and hormones. His early work showed how the pituitary gland and certain other glands are regulated by the region in the brain called the hypothalamus. The work, considered the foundation of modern endocrinology, earned him his Nobel in 1977. The prize was shared with Rosalyn Yalow, a friend and VA colleague who pioneered the field of radioimmunoassay, and hormone researcher Roger Guillemin.

In his early years as a researcher, Schally's focus was on reproductive health. He helped developed both fertility and contraceptive compounds. His work since then has pyramided on those early discoveries.

In an interview with VA Research Currents, Schally credited his scientific curiosity for fueling his long list of achievements in medical science. "This is a trait I still have," he said. "I want to know how nature controls these mechanisms."

In the 1970s, due in part to a sense of ethical responsibility, Schally shifted his focus to cancer research. "I began to see the role of hormones in breast and prostate cancer was much greater than originally demonstrated," he explains. "We had patients with various tumors. We could inject our hormones and show inhibition of the tumor. So I realized I would be a fool—even scientifically criminal—to not use in oncology some of the hormones which I discovered in the brain."

One of his key discoveries has been harnessed in the fight against cancer. The current treatment for testosterone-dependent prostate cancer is derived from a brain chemical called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), which Schally discovered. He calls LHRH the "biggest prize" of his long career. "After I gave my lecture on the discovery of LHRH to 2,000 people in San Francisco in June of 1971," he recalls, "the audience disappeared suddenly to phone the structure all over the world, in view of its expected medical importance."

Another hormone that has figured largely in Schally's work is growth hormone-releasing hormone, or GHRH. Schally and others showed that the molecule is a growth factor for several types of tumors. Several compounds developed and studied by Schally block the effects of this hormone—and thereby may thwart cancer. For example, in lab experiments his group found that a manmade compound called JMR-132 stops the spread of various types of human cancer cells—prostate, colon, ovarian, endometrial, breast—and also acts as a strong antioxidant.

Schally has also explored potential cancer treatments based on hormone analogs—modified compounds that resemble hormones but can pack 100 times the punch of their natural counterparts.

All in all, he says, "I believe we are very, very close to new methods for cancer treatment."

The Nobelist brims with excitement when describing the "smart" chemotherapies he is working to develop—therapies that zap cancer cells but leave healthy cells intact. "The beauty of these methods is that they are targeted to tumors. They go to the tumor and can destroy malignant cells. If you repeat it two, three times, you can perhaps totally destroy the tumor. In such a case, you have a treatment that comes very close to being a cure."

A number of clinical trials testing his experimental therapies are under way around the world, targeting endometrial, ovarian, breast, and prostate cancer. Some of the work focuses on difficult-to-treat forms of these diseases.

Even as they push forward on potential cancer therapies, Schally and his team are probing the role of hormones such as GHRH in other medical conditions.

In a paper published earlier in 2012 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Schally and others found that activating a GHRH receptor in rats one month after a heart attack substantially boosted cardiac function and stemmed the damage to heart muscle. The results raise the possibility that one day, heart attack patients could receive doses of the hormone to heal the damage to their hearts.

In another recent PNAS article, Schally and a different group of collaborators found that by injecting diabetic mice with a GHRH-like substance, they could increase islet cell production. This improved the animals' ability to make insulin.

All in all, Schally's work continues at a remarkable pace. In 2005, when Hurricane Katrina threatened to shut down his lab, then based at the New Orleans VA Medical Center, he moved to the Miami VA to avoid any interruption. He told a reporter from the Sun Sentinel in Fort Lauderdale: "What worried me most was my research would come to a standstill for two or three months. It's a tremendous relief to be among friends and be able to do something practical to continue my research."

Now entering his second half-century as a VA researcher, Schally shows no sign of slowing down. His total number of scientific publications to date, as author or coauthor? More than 2,380—and counting.