Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

February 12, 2014

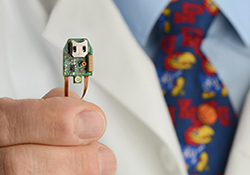

A new "microdevice" inserted in the brain of rats with traumatic brain injury enabled them to regain lost function. (Photo by Elissa Monroe/KUMC)

Until recently, doctors believed that injuries to the brain were discrete, meaning damage was isolated to the injured area. The brain was seen as a collection of independent areas, each with its own functions, scientifically speaking anyway. Researchers have since recognized that the connections between those areas are as important, if not more important, than the regions themselves.

The brain, they discovered, is more about connectivity and communication than previously suspected. This means that even isolated damage can result in other problems if the interconnections between different parts of the brain are disrupted.

Now researchers at the University of Kansas, the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland, and Case Western University have developed a way to bridge disrupted areas of the brain with a neural prosthesis.

The study, published in the December 24, 2013, issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that an artificial communication link inserted in the brain can restore functions lost as a result of TBI.

A team including Dr. Pedram Mohseni of Case Western and the Advanced Platform Technology Center at the Cleveland VA fitted a chip-containing "microdevice" into the brains of rats whose motor skills had been impaired as a result of TBI. The neural prosthesis allowed the rats to recover nearly all function. The animals were tested by their ability to reach through a narrow opening and seize a food pellet. Rats equipped with the neural prosthesis were able to complete the task 70 percent of the time, or as well as normal rats. Without the device, the injured rats were able to reach the food only 25 percent of the time.

"[The effect] was quite dramatic," team member Dr. Randolph Nudo, of the University of Kansas, said in a statement. "I have not seen anything like this. I've been in science about three decades and I have not seen anything quite so dramatic as this."

The researchers hope the device could one day pose a more efficient, inexpensive alternative to long-term therapy. In future research, they want to determine the best time for implanting the chip and find out if the brain will eventually form new connections on its own.

The findings may offer new hope not just for Veterans with TBI, but also for stroke patients, those who have had tumors removed, and others with brain damage or impairments. "We think this is a game changer," said Nudo.

The research was funded by the Department of Defense and the American Heart Association, and VA supported the fabrication of the chip in the microdevice.