Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

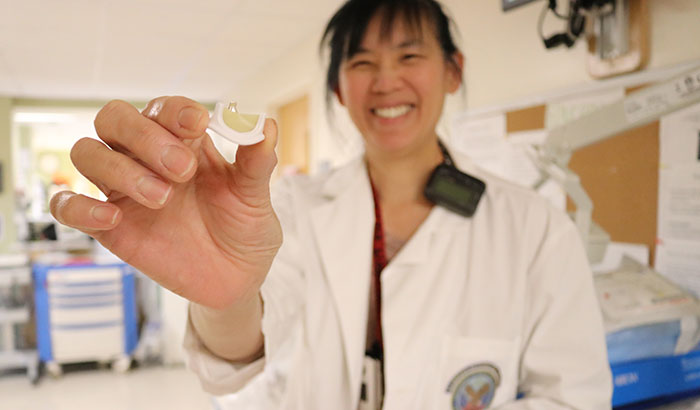

Dr. Jacquelyn Quin, a thoracic surgeon at the VA Boston Healthcare System, displays a model of a bioprosthetic valve. Bioprosthetic valves are made from cow or pig tissue. They are inserted surgically to replace aortic valves that are no longer able to properly control blood flow from the heart out to the rest of the body. (Photo by Mackenzie Adams)

January 16, 2019

By Mitch Mirkin

VA Research Communications

"Most of the valves we place now are bioprosthetic."

“You need a valve replacement.”

That’s bad enough when it’s your car mechanic talking. When it’s your cardiologist, the news is even more serious.

Replacing the heart’s aortic valve—the most common heart valve surgery—usually requires open-heart surgery. It’s a major procedure, not without risks, but the success rate is high.

The aortic valve controls blood flow from the heart out to the rest of the body. If the valve narrows, blood flow to the rest of the body is impaired. If it leaks, blood may flow back into the heart. In either case, surgery is usually the best option to stave off deadly consequences.

Bioprosthetic valves are made from cow or pig tissue. They are inserted surgically to replace aortic valves that are no longer able to properly control blood flow from the heart out to the rest of the body. (Photo by Mackenzie Adams)

A pair of recent VA studies looked at one aspect of these procedures. In both cases, the researchers wanted to see how patient outcomes differed based on which drugs doctors prescribed post-surgery to prevent blood clots. There are lots of variables that can affect which, if any, of these drugs are used—such as the patient’s health history. Also, clinical guidelines vary, even for similar patients.

One study appeared online in JAMA Surgery on Dec. 26, 2018. It found that aspirin given by itself was the most common approach, used in nearly half of cases. Compared with other common treatment options, it also appeared to be the most advantageous, provided there were no particular indications for a different therapy.

The second most popular option, used in roughly a fifth of cases, was aspirin plus the blood thinner warfarin (sold as Coumadin). That approach had no edge over aspirin alone for boosting survival at 90 days, or preventing heart attack, stroke, or other clot-related events. But it did roughly double the risk of internal bleeding, relative to aspirin alone.

Lead author Dr. Dawn Bravata says the results may lead some doctors to rethink what they prescribe after valve replacement.

“I do expect some providers to reconsider the use of the combination of warfarin plus aspirin for [bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement] patients who do not have an alternative indication for warfarin therapy, such as atrial fibrillation.”

Bravata, a physician, is a health services researcher with VA’s Center for Health Information and Communication (CHIC), and a professor of medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine.

VA Study Documents Health Risks for Burn Pit Exposures

VA center training the next generation of researchers in blood clots and inflammation

Could cholesterol medicine reduce dementia risk in seniors?

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

Her team at CHIC, plus a few collaborators elsewhere in VA, analyzed more than 9,000 procedures at 47 VA medical centers. The average age of the patients was around 69, and almost all were male.

The study included only valve replacements in which the patients received what are known as bioprosthetic, or tissue, valves. These are made from cow or pig tissue. They don’t last as many years as mechanical valves, which are made mainly from titanium and carbon. But the mechanical valves require life-long use of blood thinners to prevent dangerous clots, whereas natural-tissue valves generally don’t require long-term drug therapy.

Study co-author Dr. Jacquelyn Quin, a thoracic surgeon at the VA Boston Healthcare System, notes that in VA, “most of the valves we place now are bioprosthetic.” She says the main advantage is that they don’t demand lifelong anticoagulation meds like their mechanical counterparts.

And while they can’t match the durability of mechanical valves, they can last fairly long—sometimes up to 15 or 20 years. If they do wear out, the patient can undergo a procedure known as a TAVR—transcatheter aortic valve replacement—in which a new valve is placed via a thin tube threaded through an artery, without the need to cut open the chest.

The study included all bioprosthetic valve replacements done in VA between 2005 and 2015. “The [aortic valve replacement] numbers in VA have been steadily increasing,” says Quin. “I think that one of the main reasons driving this is an increase in valve replacements for an aging population, both in the private sector and within VA.”

A different VA study, also focused on anti-clot meds after bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, came out online in the Annals of Thoracic Surgery on Nov. 17, 2018.

This one was a systematic review study, meaning the authors culled and analyzed findings from past studies—in this case, 20 of them, including six clinical trials.

The work was funded by VA’s Evidence-Based Synthesis Program, which analyzes the existing medical literature on key issues affecting Veterans to help guide VA clinicians, managers, and policymakers.

“We were asked by VA leadership to look at this question in part because of the variation in guidelines and differing interpretations of the data,” notes Dr. Devan Kansagara, who heads an ESP research group at the VA Portland Health Care System. He was also a co-author on the study led by Bravata at CHIC.

Although the scope of the ESP research was broader, its findings were similar to Bravata’s.

“We found moderate-strength evidence that warfarin or aspirin are associated with similar outcomes after bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement,” said Kansagara. “We also found that warfarin plus aspirin might be associated with slightly lower thromboembolic [clot-related] events and mortality after bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, but the benefit was very small and potentially outweighed by a substantially increased risk of bleeding.”

He says the CHIC study that focused strictly on VA is consistent with the broader medical literature “in suggesting that aspirin alone is associated with similar thromboembolic and mortality rates [relative to aspirin plus warfarin], and likely lower bleeding, absent any compelling alternative indication for warfarin.”

Quin emphasizes that while the new findings from both studies will be informative for heart doctors in and outside VA, there are still many individual patient factors that need to be considered when prescribing antithrombotics—another term for anti-coagulants or anti-clot- drugs.

For example, while a patient who’s received a tissue replacement valve may not need any blood thinners due to clot risks associated with the valve itself, he or she may need to be on the drugs, at least for a few months, for other reasons. The most common reason is atrial fibrillation, a type of irregular heartbeat. Quin says atrial fibrillation occurs in about a third of patients after cardiac surgery.

“Each patient’s antithrombotic risk has to be individually assessed, and they have to be individually counseled accordingly—at least that’s how I do it,” says Quin. “Unfortunately, there’s no ‘one size fits all’ for this issue.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates