Office of Research & Development |

|

Women Veterans who are survivors of sexual assault can sometimes go on to develop PTSD. A VA study has demonstrated the effectiveness of Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga to help them reconnect with their bodies in a safe, nonthreatening way. (Photo for illustrative purposes only: @iStock/kali9.)

January 24, 2022

By Erica Sprey

VA Research Communications

"What this research does is give women Veterans an additional treatment option, when they choose to pursue treatment for PTSD."

Originating in India, the practice of yoga has gradually worked its way into the Western consciousness. Today, it is a common activity that is used to promote physical and emotional well-being, improve strength, and to reduce stress. One in seven people in the U.S. have practiced yoga sometime in the past 12 months, in 2017, according to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Contrary to common depictions, yoga isn't just for suburban white women. For instance, VA has embraced yoga as part of a Whole Health approach to better support Veterans who experience chronic pain or mental health challenges—in both women and men, of all racial and ethnic backgrounds. VA scientists are studying the effectiveness of yoga to remediate chronic back pain and improve quality of life in cancer survivors, among other conditions.

Now, VA investigators are examining the effectiveness of a clinical intervention, trauma-sensitive yoga, to help women Veterans who experienced military sexual trauma (MST) and went on to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Dr. Ursula Kelly is a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner and research scientist at the Atlanta VA Health Care System.

Dr. Ursula Kelly is a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner and nurse scientist at the Atlanta VA Health Care System. She also is an associate professor of nursing at Emory University in Atlanta. Throughout her career, she has worked to understand the issues facing survivors of interpersonal violence and sexual trauma.

Kelly is the principal investigator for a five-year clinical trial that sought to examine the effectiveness of a specialized form of trauma-sensitive yoga to treat women Veterans who developed PTSD in relation to MST. The trial compared the effectiveness of Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) to cognitive processing therapy (CPT)—one of several gold-standard psychotherapies used to treat PTSD.

The interim results, published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, showed that TCTSY was equivalent to CPT in relieving PTSD symptom severity in this group of women Veterans. (You can view the team's cyber-seminar presentation here.) In addition, the research team found that those in the TCTSY intervention showed an earlier reduction in PTSD symptom severity than CPT, which could help to combat a high drop-out rate for trauma-focused PTSD therapy.

"Both treatments resulted in clinically significant improvements in PTSD symptom severity, and in related outcomes. Yet, neither intervention was completely effective for everyone," says Kelly. "What this research does is give women Veterans an additional treatment option, when they choose to pursue treatment for PTSD," she adds.

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

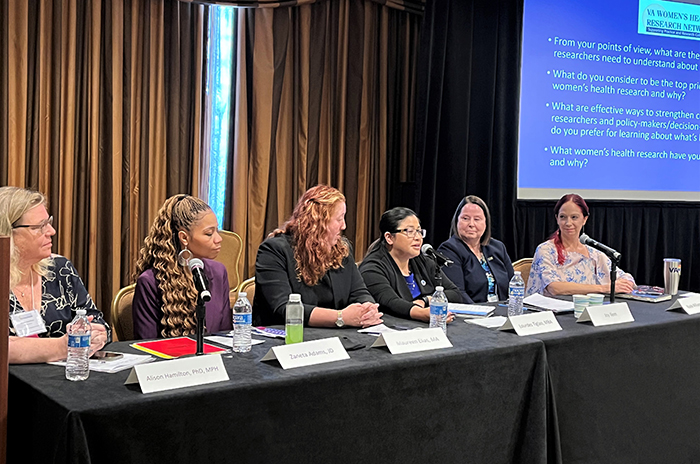

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

Self-harm is underrecognized in Gulf War Veterans

Head trauma, PTSD may increase genetic variant's impact on Alzheimer's risk

The trial had three aims: to reduce symptoms of PTSD, chronic pain, and insomnia; to improve participants' quality of life and social functioning; and to assess the mechanisms of action on PTSD—how yoga works to physiologically counteract the effects of PTSD.

The investigators enrolled over 200 women Veterans who were seeking care for PTSD related to MST at two sites: the Atlanta VA Health Care System and VA Portland Health Care System in Oregon; the number of women who were randomized was 131. The Veterans were randomized to two groups—the TCTSY arm received 10 weeks of 60-minute group yoga sessions. The CPT arm received 12 weeks of 90-minute CPT group therapy. Both groups were assessed four times during the trial—at baseline, mid-point, and two weeks and three months post-treatment—using multiple psychological measures.

The researchers also tested Veterans for biomarkers of inflammation, via blood draws, and measured heart rate variability with a wearable electronic device to assess not only the effects of PTSD but also the potential effects of yoga on these inflammatory and physiological-neurological outcomes. "With PTSD, there is inflammation in the body along with hyperreactivity—neurological pathways become dysregulated. There is a some evidence that yoga may counteract these effects on the body, on the nervous and immunological systems," says Kelly. "We are trying to determine to what extent yoga reduces symptoms of PTSD, and how it does that."

Kelly is well-versed in using complementary and integrative therapies like yoga, acupuncture, or massage. She wanted to find an alternative therapeutic approach that could help women with PTSD using a body-based intervention rather than a cognitive one. Women survivors of sexual assault often "check out" of their bodies, according to Kelly. She says she chose yoga to help these women because it is an embodied practice. The premise is that trauma happens to the body first, then affects thoughts.

"I wanted something that would help women get back in their bodies, to help regain the relationship [between mind and body]," notes Kelly. "For example, these women may not be able to feel or experience the sensations in their bodies. TCTSY focuses on interoception—developing an awareness of bodily sensations." Interoceptive signals are transmitted by the nervous system to help the brain process sensory input and internal body states, like heart rate, respiration, or hunger.

TCTSY is a specific form of trauma-sensitive yoga that was developed by David Emerson and Jennifer Turner, co-directors of the Center for Trauma and Embodiment at the Justice Resource Institute (JRI) in Brookline, Massachusetts. The center works with women and men who have experienced complex trauma, like childhood sexual abuse. "For many survivors, living in their body in the aftermath of trauma is incredibly challenging, for a number of reasons," says Turner.

TCTSY is based on Hatha yoga, "where participants engage in a series of physical forms and movements. Elements of standard Hatha yoga are modified to cultivate a more positive relationship to one's body. Unlike many public yoga classes, TCTSY does not use physical hands-on adjustments," according to the JRI. The practice is invitational in nature, making sure that participants maintain control over their own bodies. (You can listen to a video explaining TCTSY here.)

"The body is a piece of our experience that was left out of the therapy room, in a way that wasn't helpful for people. So, TCTSY was a way to bring the body into the process," notes Emerson.

For instance, TCTSY facilitators may focus a session on "making choices," by inviting women to raise their arms over their head, rather than telling them to do so. Participants also have the choice of taking "effective action," which is doing something they did not think they could do. The goal is to take action, not to be fully successful in attempting a yoga pose or form.

"One aspect of TCTSY is a very intentional use of language," says Kelly. "It is completely invitational. So, the instructor might say, 'I invite you to, if you are comfortable, sit in a cross-legged position, close your eyes, or stare at the floor.'"

Women, or men, who experience sexual trauma—like childhood sexual abuse—often experience betrayal trauma. When a child, or intimate partner, depends on their abuser for caregiving or financial or emotional security, that can set up a psychological conflict. The abuser has violated the individual's sense of trust and well-being, but is still a needed caregiver or provider. To preserve that relationship, the victim will sometimes deny to themselves that a harm has occurred.

Therapy to re-establish a sense of safety typically begins by focusing on control of the body and gradually moves to control of the environment, writes Dr. Judith Herman, an expert in betrayal trauma. She notes that sexual assault survivors often feel unsafe in their bodies and experience difficulties with "basic health needs, regulation of bodily functions such as sleep, eating, and exercise, management of posttraumatic symptoms, and abstinence from substance abuse."

A similar dynamic can occur in military settings, where abusers may be in a position of power over their victims. However, Kelly says, it is important to note that not all service members who experience MST will go on to develop PTSD. In some instances, people are able to draw on inner resilience, which can help them cope with the effects of their trauma, or have sufficient external support so that the trauma doesn't become disabling.

VA is a leader in the development of evidence-based approaches to treat Veterans with PTSD. It is a complex condition that is often difficult to treat. While current therapies can be effective, there is a high drop-out rate among Veterans. That is why Kelly's team is seeking new treatment modalities for PTSD specifically related to sexual trauma. Having access to multiple evidence-based therapies gives therapists and their patients more choices. "What works well for one person, may not work well for another," notes Kelly.

Dr. Belle Zaccari is a clinician researcher and psychologist at the VA Portland Health Care System in Oregon.

Dr. Belle Zaccari is a clinician researcher and psychologist at the VA Portland Health Care System in Oregon and works for the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC). She has extensive experience in using evidence-based treatments to treat PTSD. Her research focuses on complementary and integrative health therapies like Tai Chi or yoga to treat PTSD or chronic pain. She is the site principal investigator in Portland, Oregon, on the TCTSY clinical trial.

PTSD is characterized by emotional distress and functional impairment resulting from exposure to a traumatic or stressful event, says Zaccari. "I would note that women Veterans with PTSD related to MST have specific needs. We now know that people who have experienced gender-based or interpersonal violence have specific needs."

VA uses evidence-based, trauma-focused therapies to treat PTSD in Veterans—meaning treatment focuses on processing memories of the traumatic event in a safe manner, according to the National Center for PTSD.

Zaccari says that VA supported evidence-based treatments for PTSD can include:

Both Zaccari and Kelly recognize that further studies on TCTSY are needed in order to find the best ways to implement the treatment on a national level. The study authors note that TCTSY's potential to effectively treat PTSD has great relevance for policy makers—the therapy costs less to administer than psychotherapy, is simpler to deliver, and is easier for Veterans to access.

"In our trial, the benefit of yoga was that symptoms improved more quickly than with CPT. Even at mid-point, for TCTSY, the PTSD symptoms dropped in severity, very dramatically," says Kelly. "Women improved faster and didn't suffer as long. If you get better more quickly, you are more inclined to stay in therapy and see it through."

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates