Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

Veterans make up about 8 percent of the arrestee, jail, prison, and community-supervision population. (Photo for illustrative purposes only. ©iStock/mediaphotos)

February 28, 2019

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

Army Veteran resurrects once-troubled life, provides support to Vets in correctional settings

Some 300 professionals in the fields of correctional health care and juvenile justice will gather for a conference in March to examine emerging research and relevant policy issues at a time when the U.S. has the greatest prison population in the world by far.

Some of the topics touch on justice-involved Veterans. The term describes former service members who have been detained by or are under the watch of the criminal justice system. Veterans make up about 8 percent of the arrestee, jail, prison, and community-supervision population.

The Academic Consortium on Criminal Justice Health, which aims to “advance the science and practice of health care” for those in the criminal justice system, is hosting the conference. The group’s mission is similar to that of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, but the consortium takes a broader view of the criminal justice system by considering settings in addition to incarceration, such as courts and probation or parole.

The conference is set for March 21 and 22 in Las Vegas. It will provide a forum for researchers, clinicians, educators, policymakers, and others to explore whether improvements to community programs help to decrease recidivism, which is the tendency of a convicted person to re-offend; what practices can reduce self-injury behaviors and suicide rates; what strategies are useful in preventing relapses in substance abuse; and what approaches will help incarcerated people adhere to chronic illness treatment.

The agenda includes Veteran-related presentations on 15 topics by VA researchers, former service members, and specialists from two VA programs that provide outreach to Vets in criminal justice settings: the Health Care for Re-entry Veterans (HCRV) program, which assists Veterans who are in state or federal prison; and the Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) program, which helps Veterans who are in courts and jails. Both programs try to connect justice-involved Veterans with medical, mental health, and substance use disorder treatment, as well as housing and other support programs.

"Veterans involved in the legal system have more extensive mental health and substance use disorders and social problems than those without legal involvement."

More than half of justice-involved Veterans have mental health problems—namely PTSD, depression, or high anxiety—or substance-abuse disorders, most notably alcohol or cocaine addiction. A large percentage of these Veterans are also homeless or at-risk for homelessness, and many others face such challenges as finding work and reintegrating into society.

Below is a sampling of the Veteran-related topics on the agenda.

Drug overdose is the No. 1 cause of death among adults who previously served time in prisons and jails. A large percentage of this population abuses opioids.

Opioids are a class of drugs that include pain relievers available by prescription, but which are sometimes used recklessly because of the euphoric feeling they induce. Buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone are the only drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat opioid use disorder. Research has shown that they reduce the death rate among opioid-addicted patients by at least a half and are much more effective at keeping people in treatment than non-medication approaches.

A four-person panel will discuss trends with justice-involved Veterans who are receiving drugs for opioid addiction in the VA system, with a look at their death rates at the one-year mark. Justice-involved Veterans may have less access to opioid-addiction medications than former service members who haven’t broken the law. Case in point: About two-thirds of justice-involved Veterans treated in VA facilities didn’t receive drugs for opioid disorders in fiscal year 2012, according to the latest statistics.

Dr. Jay Gorman

Suicide prevention care

VA Researcher Named One of U.S.’ Top Female Scientists

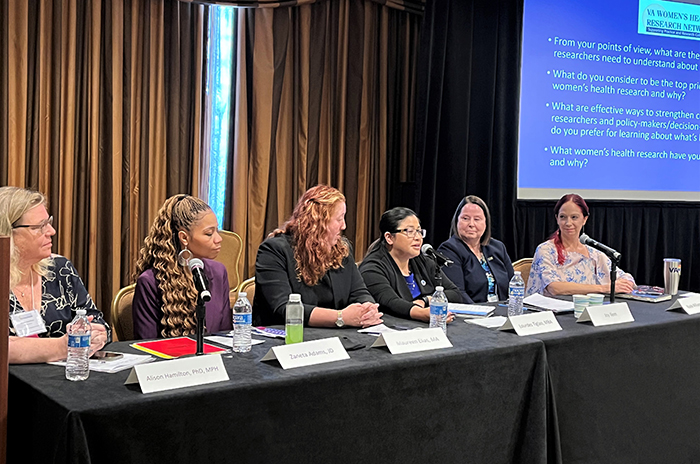

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

The panel will discuss reasons identified in interviews for the differences in access to opioid-addiction drugs, and how those findings are shaping VA’s response to the White House initiative to address the nation’s opioid epidemic. The initiative includes $6 billion in funding over two years to fight opioid abuse. Ultimately, researchers say, improving access to opioid-addiction drugs is imperative for helping justice-involved Veterans improve their health and decreasing their risk of committing repeat offenses and experiencing death.

The panel includes Dr. Andrea Finlay of the Center for Innovation to Implementation at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in California; Erica Morse, a research associate at Kaiser Permanente; Susann Adams, a VJO and HCRV specialist at the VA Long Beach Healthcare System in California; and Jessica Blue-Howells of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Blue-Howells is the national coordinator for the HCRV program and Project CHALENG, which aims to meet the needs of homeless Veterans.

VA can’t offer legal services. But VA medical centers can provide space to host legal service clinics, which are designed to help Veterans obtain VA benefits and address problems in getting medical treatment. These clinics help address barriers to receiving health care, such as disabilities, driver’s license reinstatement, and other challenges unrelated to criminal law.

More than 100 VA facilities house legal clinics, the first of which appeared in 2008. They serve an average of nearly 1,700 Veterans per month in total and are staffed by people from legal aid groups, law firms, and bar associations, and by law students.

This presentation will provide perspectives on how VA-housed legal clinics are impacting the lives of justice-involved Veterans. The presenters are Emmeline Taylor and Amia Nash of the Center for Innovation to Implementation at VA Palo Alto, and Elizabeth Brett, a VJO specialist at the Cincinnati VA Medical Center.

The panel will elaborate on a VA-funded pilot project that examined VA-housed legal clinics as a potential gateway to VA mental health and substance use treatment for Veterans with legal problems.

“Generally, this topic is gaining momentum because Veterans involved in the legal system have more extensive mental health and substance use disorders and social problems than those without legal involvement,” Taylor says. “Also, Veterans frequently report legal difficulties related to obtaining and using VA health care benefits. Research has found that resolution of patients’ civil legal problems is associated with lower acute health care costs.”

The panel will also focus on survey data related to legal concerns and health care among Veterans using non-VA legal clinic services, and the challenges and successes involving the program at the Cincinnati VA. “We hope to bring perspectives from VA to the broader correctional health community to work together to improve coordination between the health care system and the legal system,” Taylor says.

Veterans treatment courts serve Veterans who are charged with violent or non-violent offenses. Most of these courts require Vets to be diagnosed with a mental health or substance abuse disorder. Regarding the latter, those sentenced must make regular court appearances, attend all substance treatment sessions, and undergo frequent and random testing for drugs and alcohol, before they are eligible for release.

A three-person panel will discuss Veterans treatment courts, with a special focus on the

Veterans Treatment Court Improvement Act of 2018. The bill requires VA to hire at least 50 VJO specialists, each of whom must serve as part of a justice team in a Veterans treatment court or other Veteran-focused court. The bill also calls for the Government Accountability Office to report to Congress on the effectiveness of the VJO program.

The panel includes two VJO specialists, Dr. Matthew Stimmel of VA Palo Alto and Machele Huff of the Salem VA Medical Center, as well as Army Veteran Ray Perez, a peer support specialist at the Phoenix VA Health Care System. After leaving the military in 2001, Perez became addicted to alcohol and was imprisoned for breaking the law. He spent time in Veterans treatment court and underwent court-ordered mental health treatment (see sidebar).

Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT) is a group-based cognitive behavioral program for people in the criminal justice system. It is intended to reduce the risk of repeat offenses by addressing a person’s tendencies toward “criminogenic thinking,” which relates to an inability to control one’s impulses, and blaming others for your problems.

MRT was developed outside of VA and has mainly been tested and implemented in jails and prisons, as well as in parole and probation services. Officials in the VJO program have been interested in adopting MRT as an evidence-based practice for justice-involved Veterans.

Dr. Daniel Blonigen of the Center for Innovation to Implementation at VA Palo Alto will elaborate on the use of MRT in non-correctional settings. With support from VJO, he was funded by VA to conduct a large multisite trial of MRT for justice-involved Veterans enrolled in VA Mental Health Residential Treatment Programs. They provide residential, rehabilitative, and clinical care to Veterans with a wide range of problems and illnesses, including mental health disorders and homelessness.

“These residential programs are very different types of settings than the correctional settings for which MRT was initially designed,” says Blonigen, who is also a clinical assistant professor affiliated with Stanford University. “My presentation will focus mainly on the lessons we’ve learned about the barriers and advantages to implementing MRT in a non-correctional setting, such as a VA treatment program.”

Blonigen will also discuss his study that is aimed at identifying why VA medical centers did or didn’t adopt MRT following a national training initiative in 2016 and 2017. The findings, as well as those from the multisite trial, will help develop a strategy that VA facilities can use in the future to implement MRT and to involve community-based facilities in the process, such as Veterans treatment courts, he says.

Unemployment is one of the most significant consequences facing those being released from prison. Estimates are that only 52 percent of former detainees will have competitive employment six months after being let go from a correctional facility. That figure is worse for people with mental illness.

Dr. James LePage, the chief of research at the VA North Texas Health Care System, will give a presentation on the About Face program, one of a series of VA vocational initiatives. It’s designed to improve job prospects for Veterans who have been convicted of felonies by providing skills to search for and find employment.

A VA-funded trial led by LePage found that Veterans who used About Face in a group setting were twice as successful in finding competitive employment, compared with those in usual care and users of self-help materials. Currently, he and his colleagues at the North Texas VA are testing the program through an online and telerehab interface. They hope to reach Veterans in rural areas, those with transportation or other mobility difficulties, and Vets who resist coming to a local VA hospital or clinic to take part in the program.

LePage says the Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2018 will have no immediate impact on the About Face program. The bill amends previous legislation to support a series of evidence-based initiatives that are designed to meet the needs of youth who come in contact with the criminal justice system. But he speculates that the act will have a “downstream” effect by ultimately reducing the number of people, including Veterans, who are incarcerated as adults.

Ray Perez is a peer support specialist with the Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) program at the Phoenix VA. (Photo by Stacy Jonsgaard)

It was just him and four walls. They surrounded Army Veteran Ray Perez while he was in solitary confinement six years ago in a county jail in Arizona.

Perez had violated his Veterans treatment court probation by drinking alcohol excessively, which followed years of him neglecting his life. He had become addicted to alcohol, using it to self-medicate, he was homeless for some time, and he blacked out and crashed his car into a bus stop in Phoenix. Nobody, including Perez, was hurt in the crash. But he was charged with 15 offenses, including endangering the public, driving under the influence of alcohol, and attempted aggravated assault on a police officer. He spent four months in jail, before signing a deal that led him to Veterans treatment court probation.

He came to a rude realization in solitary confinement: It’s easy to lose track of time.

“The only time you know is when it’s breakfast or dinner time,” he says. “For breakfast, they open up the little trap window and throw you milk, an orange, and two pieces of bread. At dinner time, they’ll open up your trap and give you a plate of slop.”

Once a senior correctional officer with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons and a detention officer with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Perez reflected in solitary confinement on why he had taken such a precipitous fall in life.

“I had a lot of time on my hands,” he says. “In the end, everything was revolving around my abuse of alcohol that started immediately after my discharge from the military [in 2001]. I ended up becoming the person that I had been protecting society from in the decade that I had been out of the Army. I was married. My children needed me. I was self-sabotaging. I had hit rock bottom. I had been homeless on the streets. I didn’t want that anymore.

“This is when lightning struck. I told myself, 'I can’t do this anymore. I can’t.’ So I started rebuilding my foundation.”

He began by halting his consumption of alcohol. Officials at Veterans treatment court, meanwhile, ordered him to take part in rehab programs and sent him to Crossroads, a transitional housing program for Veterans and others who are struggling with substance abuse. He checked in to the mental health clinic at the Phoenix VA, where he spilled his emotions to a specialist on what had led him to this ominous point. “I spoke about everything that I had been carrying inside of me for all of these years,” he says.

“The mental health specialist diagnosed me with a case of PTSD from my days in the Army,” he says. “She helped me understand everything that I had been experiencing. I went to intense outpatient treatment. I’d go to VA for classes three times a week.”

Perez was eventually tapped to do housekeeping at the Phoenix VA through the Compensated Work Therapy program, sweeping and mopping floors. He re-acclimated himself to an environment of military folks, a camaraderie that he sorely missed from his three-year stint in the Army. He earned letters of recommendation, including one from the priest at the Phoenix VA.

VA was reluctant to hire him full-time because of his previous conviction. But he submitted an appeal.

“I said, 'Yes, there’s some bad stuff that I’ve done, but there’s also a lot of good I’ve done in my life,’” he recalls. “I showed them all of my certificates from the military and federal law enforcement, and the letter from the priest.”

In October 2014, Perez began working as a medical support assistant at the Phoenix VA. In August 2015, the two-year anniversary of his sobriety, he transferred to the VA Community Resource and Referral Center (CRRC) at the Phoenix VA as a peer support specialist. CRRCs provide Veterans who are homeless and at risk of homelessness with critical services. He began going to the same shelters where he lived while he was homeless.

“People started recognizing me, and I shared my story with them,” he says.

In 2016, Perez transferred to the Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) program at the Phoenix VA, where his life has come “full circle,” as he put it. The VJO program helps Veterans who are in courts and jails.

“Our community resource and referral center coordinator, Penny Miller, was my case manager when I was in Veterans treatment court,” he says. “She’d seen me shackled up. She knew me when I was going through my struggles. Now, I work for her. She’s like, 'I can’t think of anybody other than you to do the work. You’ve been through that program. You graduated from that program.’”

Perez travels with colleagues to courts, jails, and prisons in Arizona, where about 3,000 Veterans are incarcerated. He shares his life story with former service members, trying to inspire them with hope that change is possible, and helps them connect with health and social services. He assists them, for instance, with receiving any compensation due them from VA. Veterans with a service-connected monthly disability benefit are entitled to receive 10 percent of that amount while in prison.

He says he’s the first VA peer support specialist in the country to travel to correctional facilities with a specialist from the Health Care for Re-entry Veterans program, which assists Vets who are in state or federal prison.

Perez also works with the Arizona Department of Corrections parole team and the Maricopa County probation team in the Phoenix area. Plus, he’s involved with HUD-VASH, a collaboration between VA and U.S. Housing and Urban Development to help homeless Veterans and their families find permanent homes.

“I’ve been back to the same county jail where I was locked up,” he says. “I lead a group called 'Breaking Down Barriers,’ and I facilitate relaxation therapy groups. I get to talk about my life. I say, 'Hey, guys, I’ve been here, the same exact spot where you guys are at.’ It’s a blessing to be able to do that.”

Perez has also launched a non-profit group called Operation Restoring Veteran Hope. The heart of the program is a weekend retreat for Veterans who have spent time in correctional facilities. The retreats offer the opportunity for a healthy lifestyle in a positive environment. A few months ago, Perez coordinated a retreat for some 100 former justice-involved Veterans at the St. Joseph’s Youth Camp, in a picturesque setting in the mountains in northern Arizona.

“I’m very humbled,” he says. “I’ve been down some very dark roads. I wouldn’t wish that upon anyone.”

--- Mike Richman

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates