Office of Research & Development |

|

An explosive ordnance disposal technician performs a sweep with a metal detector during a post-blast analysis at a Marine training site in California. Blast exposure is common among service members, but its chronic psychiatric effects are not well-understood. (Photo by Marine Lance Cpl. Levi Schultz).

February 8, 2022

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

However, it's clear that blast exposure doesn't need to cause a mild TBI to have a negative effect.

A new VA study finds that blast exposure is related to mental health symptoms in combat Veterans beyond the effects of mild traumatic brain injury or PTSD.

The findings appeared in the Journal of Psychiatric Research in September 2021.

VA Researcher Named One of U.S.’ Top Female Scientists

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

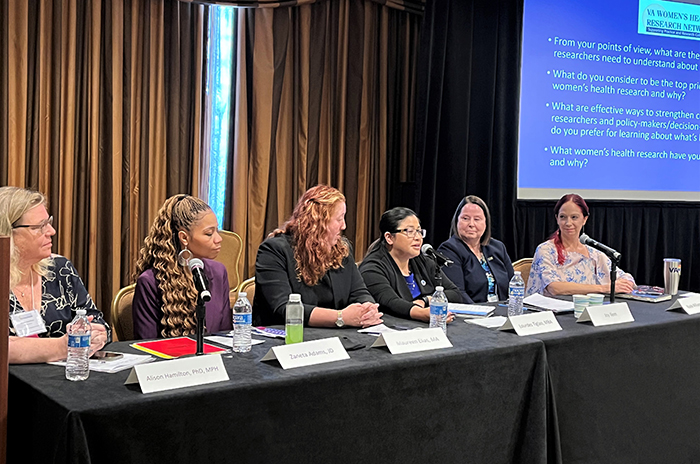

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

The study, believed to be the first of its kind because of how it evaluated blast exposure, involved interviews and self-report measures. It included 275 Veterans who experienced combat during the post-9/11 conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. More than 70% had a history of blast exposure, which was defined as any notable pressure wave resulting from an explosion. Nearly 50% had been diagnosed with a mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI), which is essentially a concussion, and 30% with PTSD.

“Exposure to blast is an independent factor influencing psychiatric symptoms in Veterans beyond PTSD and mild TBI,” the researchers write. “Blast exposure … should be considered in the [cause] of psychiatric symptom presentation and complaints. Further, severity of psychological distress due to the combat environment may explain how blast exposure [impacts] the relationship between mild TBI and symptom outcomes.”

Dr. Sarah Martindale, a research scientist at the W.G. (Bill) Hefner VA Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina, and a member of VA’s Mid-Atlantic MIRECC (Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center), led the study. Dr. Jared Rowland, Dr. Anna Ord, and Lakeysha Rule, all of whom are also affiliated with the Salisbury VA and the Mid-Atlantic MIRECC, co-authored the paper.

Martindale and her colleagues expected blast exposure to impact the Veterans’ mental state but not to the extent it did.

Blast exposure is common among service members. But its chronic psychiatric effects are not well-understood. Until recently, most available research on the effects of blast exposure relied on interviews to diagnose traumatic brain injury, the signature wound from the post-9/11 conflicts. These interviews have evaluated blast exposure within the context of a TBI due to a blast, but not characteristics of the blast itself, according to Martindale.

Plus, there’s nothing definitive as to what constitutes blast exposure, creating a challenge all its own when studying the topic of blasts. However, it’s clear that blast exposure doesn’t need to cause a mild TBI to have a negative effect.

“Each group studying blast exposure in humans defines it differently, some based on distance, some based on the measurement of the blast wave, and some based on injury,” says Rowland, a research psychologist at the Salisbury VA. “But there is not a widely accepted or used definition of blast exposure. The long answer is complex. Pre-clinical research on animal models has shown that exposure to a blast wave of a certain intensity will cause damage to the brain and internal organs. The intensity of the blast wave fades quickly with the distance from the blast, so that critical level of intensity can occur at different distances depending on the strength of the blast, the environment in which it occurs, and the protective factors that are present.”

Those factors include body armor and ear and eye protection, as well as being behind cover or the existence of an object between the person and the blast.

“We don’t know if there’s a ‘mild blast exposure’ similar to mild TBI, in which people experience symptoms that may persist when there is no clear brain damage,” Rowland says. “The repetitive nature of occupational blast exposures, which are typically low-level and considered safe, also complicates the situation. This is something that pre-clinical work is only beginning to explore. We don’t answer that question in this study. Instead, we examine how exposure to the increasing severity of blast is related to the symptoms, rather than trying to pick a threshold of exposure that we randomly label as `blast exposure.’”

Data for the study were collected as part of a project funded by the Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC), a VA-DOD research initiative. CENC focuses mainly on understanding the lifetime impacts of military service and mild TBI, with respect to mental health disorders like PTSD and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In 2019, CENC was renamed the Long-term Impact of Military Relevant Brain Injury Consortium-Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC), which is now the world’s largest research consortium dedicated to the study of mild TBI.

The researchers designed the Salisbury VA study to examine the effects of blast exposure on psychiatric symptoms beyond the effects of PTSD and TBI. They used an interview they created in 2020 to evaluate one’s history of blast exposure in training, combat, and civilian environments. The Salisbury blast interview captures characteristics unique to blast exposure, including distance, position, munitions, and protective factors, as well as the participants’ perception of things like the pressure wave, wind, and temperature change for each event.

“We have found that people are pretty good at recalling the details of blast events,” Rowland says. “Most larger blast events are rather memorable for people, as long as they remained conscious.”

In addition, “We have seen that pressure experienced from a blast exposure was the best measure of severity,” Martindale says. “We used this pressure rating in the current analyses to understand the strength of the relationship between blast exposure and symptoms that our Veteran participants reported.”

Separately, the Veterans completed interviews on their history of PTSD and TBI. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), considered the benchmark for assessing PTSD symptoms, determined current and lifetime PTSD diagnosis. Self-reported psychiatric and health outcomes included symptoms related to PTSD, depression, and neurobehavioral complaints, which include aggression, a lack of motivation, and the inability to plan and execute actions. Sleep quality, pain, and quality of life were also evaluated.

The results indicated that greater blast exposure severity was linked to an increase in chronic health symptoms, such as PTSD, depression, and neurobehavioral complaints, even after adjustments for the effects of a PTSD diagnosis and mild TBI. Additionally, blast exposure accounted for major aspects of the relationship between the history of deployment mild TBI and behavioral health outcomes.

Despite these findings, Martindale cautions that the study of blast is in its infancy, and that the way blast exposure results in increased psychiatric symptoms has not been identified. It’s possible, she notes, that blast exposure has direct effects on the brain—even in the absence of a full-blown brain injury—that lead to these changes. However, it’s also possible that the severity of psychological distress due to combat may play an important role.

“There is strong evidence that blast exposure affects the brain, and that these effects likely influence behavior,” Martindale says. “However, we must consider several factors in a combat environment that may explain these outcomes other than blast exposure or PTSD or TBI. For example, service members are largely resilient to developing PTSD. However, some blast events are very intense, such as in a combat situation. The stress of repeated, high-level, incoming blasts paired with other factors, such as a lack of sleep, dehydration, environmental heat, and chemical exposures, may lead to the development of symptoms that don’t necessarily fit PTSD criteria or require treatment but are still present. Perhaps it’s one of these other circumstantial or physiological factors that lead to negative outcomes.”

Rowland agrees with that assessment.

“Additionally, when blast exposure results in PTSD, it doesn’t necessarily need to be due to changes in the brain,” he says. “We’ve seen that experiencing a TBI during deployment increases the risk of developing PTSD later, even after considering related factors like combat. Though we assume that something about how a TBI changes brain function and leads to developing PTSD, until we know that for certain we should continue to consider alternate explanations. For example, a blast event in a combat scenario is probably going to be scary and traumatic.

“Think about a base getting hit with mortars and rockets and how helpless that must feel. Then add in a blast happening somewhere around you, maybe a direct hit on the bunker you are in just before the door closes. This event could alter brain function and lead to the development of symptoms. Or maybe this whole episode is just a little more traumatic than if that blast wasn’t quite so close. Or maybe it’s both. This early in the study of blast we want to make sure our science is sound, and that we are not jumping to conclusions without clear, robust, and reliable data to support them.”

Currently, Martindale and Rowland are working with colleagues in VA and DOD to help develop a clear definition of blast exposure. She explains that DOD considers factors like the reading of helmet sensors to provide measurements of the blast, while VA relies more on the personal accounts of Veterans. Current congressional mandates call for this definition with a large focus on active-duty personnel, she says, but VA’s goal is to ensure that Veterans are also well-represented. In the end, the definition of blast exposure should be the same for DOD and VA, with a focus on measurable metrics and personal stories of what happened during the blast, she notes.

The researchers are also following up on their finding that blast exposure was related to a decrease in size of the hippocampus, an area of the brain critical for memory and cognitive performance, among the 275 Veterans who took part in the Salisbury study. “This was very similar to preclinical research that has been done and has some worrisome implications,” Martindale says. “We are working to understand how blast exposure affects brain structure, brain function, behavior, and symptoms.”

Rowland: “The most important thing we can contribute to the study of blast is an understanding of who is at risk for poor outcomes following blast exposure, or potentially due to their history of blast exposure. The reason for trying to understand how blast exposure is related to outcomes, such as psychiatric symptoms, is to prevent them from happening and to have effective treatments when they do. We can’t do that until we understand the circumstances and contributing factors that lead to these negative outcomes. By identifying the characteristics that lead to negative outcomes, we are also identifying targets for treatment.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates