Office of Research & Development |

|

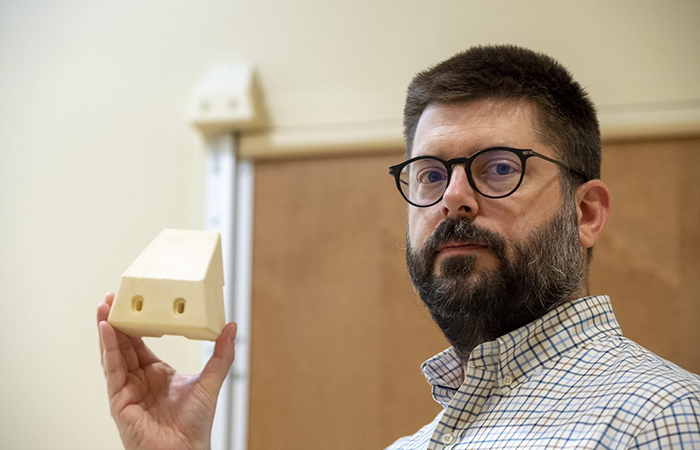

Frank Moore, the suicide prevention coordinator at VA Pittsburgh, displays the 3D block that was installed on all of the bathroom doors in patient rooms in the facility’s mental health wing to prevent a potential hanging. (Photo by Bill George)

April 27, 2021

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

In hospital rooms designated for suicidal patients, bathrooms are considered a dangerous area where people may try to kill themselves because they have more privacy. Those areas, including the bathroom door, must be designed so it’s impossible to wrap a rope, a sheet, a belt, or any other item around an anchor point that can support a hanging.

In VA, most doors in mental health units leading from the bedroom to the bathroom are sized down and made of a flimsy breakaway material unable to hold weight. An anchor point needs to support only about 10 pounds of weight around the neck to work.

The VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System has a different type of setup. The nearly 80 rooms in its mental health wing include full length, three-inch-thick bathroom doors.

More than a year ago, a staff member spotted a vulnerable area on those doors that patients could use to try to hang themselves. The hospital responded by installing a device that would make it virtually impossible for someone to do so.

"It’s not often that research and development lead to directly saving lives. That’s exactly what our team at HERL, in collaboration with our teammates at VA Pittsburgh, has done through this invention and its implementation."

The Human Engineering Research Laboratories, a collaborative effort between VA Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh, designed and produced the device. The 3D-printed block, which is about the size of a coffee cup, is placed in the corner at the top of a door to prevent it from being used as a ligature point—an area where a piece of material can be bound and tied tightly. The block has been installed on all of the bathroom doors in the rooms in the mental health wing.

An alarm bar that would alert hospital workers if someone tried to die by suicide has run across the top of all in-suite bathroom and corridor doors in the wing since it was built in 2015. But the additional device was needed to eliminate the vulnerability posed by the remaining anchor point. The device will set off the alarm bar if someone tries to carry out a hanging.

James MacAulay, the supervisory general engineer at VA Pittsburgh, took the lead in pushing for the new device, which brings the alarm system into play and provides enough warning time for hospital staff to respond to a potential hanging. “The device, in itself, doesn’t remove the pinch point because the gap at the top of the door is still there,” he says. “All it’s doing is moving the anti-ligature potential to a point where we’re protected.”

VA Researcher Named One of U.S.’ Top Female Scientists

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

Self-harm is underrecognized in Gulf War Veterans

MacAulay is unaware if other VA medical centers are set up to benefit from a similar installation.

“Not all VA hospitals are created equal,” he says. “We have very nice rooms with in-suite bathrooms. I don’t know if all VAs have that. It’s really the bathroom door that’s affected here. The other door that we protect is the door going into the room from the main hallway. We also have an anti-ligature alarm bar on that one for protection if anyone tries to use it. That one is a little less scary because it’s on the outside in the corridor. The bathroom one is the one that’s hidden. It’s inside the typically closed corridor door between where the patient sleeps and the bathroom. Not all VA hospitals have that setup.”

In 2019, following a hanging on the inside of a corridor door at a VA hospital, VA required the use of over-the-door alarms on corridor doors of patient rooms in acute mental health units. No such mandate exists for bathroom doors in patient rooms. But the VA Mental Health Environment of Care Checklist requires interior bathroom doors to be void of anchor points (see sidebar). A VA directive calls for compliance with the checklist.

The most common way for someone to attempt suicide in a mental health unit is to take a sheet or other lanyard and put it over the top of a door, then shut the door and hang on the inside of the door, says Dr. Peter Mills, a psychologist with the VA National Center for Patient Safety. Patients have also died from drug overdose and asphyxiation, he says.

Before the installation of the 3D block at VA Pittsburgh, no pattern existed of patients using the unprotected area on the bathroom door to attempt suicide, MacAulay notes. A hospital worker simply noticed the vulnerability and brought it to the attention of the staff.

“It came down to what to do about it,” MacAulay says. “We had meetings with the behavioral health staff, with the suicide prevention staff. It was kind of a joint push that we needed to do something about it once it had been discovered. We discussed lots of things, everything from just removing the doors completely to trimming the doors down so you would have a more open area on top that would eliminate the potential for a pinch point.”

Instead, MacAulay drew up a 2D object to block off the pinch point and fit the dimensions around the door frame. He first used a block of wood to gain an idea of what a more refined design may look like. “We had to make a tight design that also was not creating a ligature potential in itself,” he says. “We didn’t want to put something up there obviously that somebody could still use to tie or wrap something around.”

MacAulay then contacted Dr. Garrett Grindle, the associate director of engineering at the Human Engineering Research Laboratories (HERL). HERL does research, development, and testing on an assortment of technologies and uses 3D printers to design and create prostheses and other assistive devices. MacAulay asked Grindle if HERL would use his 2D design to create a prototype of the 3D device.

“He jumped all over this as soon as he heard what we’re doing,” MacAulay said of Grindle.

The 3D block removes an anchor point next to the alarm bar that runs across the top of the door to notify hospital staff of a suicide attempt. (Photo by Bill George)

Grindle and his staff worked with the facilities management service at VA Pittsburgh to convert the 2D design into a 3D model. Since HERL already had the computerized files of the device and 3D printers, MacAulay commissioned HERL to print them in large quantity. HERL created 90 over a three-week period, more than enough for the mental health wing at VA Pittsburgh, which has three floors and 26 rooms per floor. The blocks are made out of nylon, which is strong enough to do the job, he says.

“Jim and his people in facilities at VA Pittsburgh are a great group of people,” Grindle says. “It was nice to have the opportunity to work with them and find a non-conventional way to combine our resources to serve our Veterans.”

With the new block in place, the electrical alarm bar is positioned to detect a rope, sheet, or any other lanyard all along the top of the door.

“Exactly,” MacAulay says. “It basically brings that bar into play. Without this device, a knot would kind of be tucked away, and the bar would never be able to sense it. But with the block there, you block off that opening right in that area. So if anybody were to throw something up there, the electronic sensor would pick it up.”

Dr. Rory Cooper, a bioengineer and the director of HERL, says other VA medical centers could use the new 3D device, but they have not yet done so to the best of his knowledge. He knows of no research that is planned on the device, which he calls a “quality assurance project.”

“It’s not often that research and development lead to directly saving lives,” Cooper says. “That’s exactly what our team at HERL, in collaboration with our teammates at VA Pittsburgh, has done through this invention and its implementation.”

Suicide prevention is VA’s top clinical priority. An alarming number of Veterans—more than 17—are taking their lives on a daily basis.

Significant VA resources are devoted to preventing the suicide of Veterans, who can be at risk for various reasons. One area where VA has made major strides in recent years is in preventing inpatient suicide deaths. VA inpatient suicides in short-term mental health units have dropped from more than four per 100,000 admissions from over a decade ago, to less than one per 100,000 admissions, a difference of about 82%.

Last year, there were no suicide deaths in VA mental health units.

VA officials credit the Mental Health Environment of Care Checklist with the precipitous decline. In 2007, a multidisciplinary group of VA employees developed the program to review inpatient mental health units and eliminate hazards that could increase the chances of patient suicide or self-harm. The group focused on architectural changes, with analyses suggesting that structural hazards, such as anchor points like a hook on the wall or a ceiling vent, were linked to most attempted or completed suicides.

Following implementation of the program, each VA hospital with a psychiatric unit treating suicidal patients began using the checklist to report the potential dangers that could allow one to take his or her life. The checklist asks questions, such as whether beds, walls, and ceiling vents are free of anchor points for hanging. Other potential hazards include non-shatterproof glass and non-tamper-resistant electrical outlets.

Dr. Peter Mills, a psychologist for the VA National Center for Patient Safety, believes it’s very hard for a patient in a VA mental health unit to find a way to take his or her own life because of the precautions in the checklist. He led a VA internal training video that reviewed the safety measures used inside and outside of a patient’s room in a mental health wing to prevent suicides. They included the avoidance of anchor points and the flush mounting of all objects to the wall so nothing can be used as a hook for a potential hanging.

“Once patients are in the mental health unit, the expectation is that they will be kept safe, not just by environmental regulations like over the door alarms,” Mills says. “Staff members are routinely rounding every 15 minutes checking on patients. Patients are evaluated by psychiatrists and psychologists to see what their risk is. If patients are at very high risk, they’re put on a one-to-one observation until they become less suicidal.

“Acute suicidality is a fairly short phase,” he adds. “If we can get our arms around patients and bring them into a mental health unit and help them with psycho-social needs, give them some treatment … maybe they need legal help, maybe they need a medication adjustment to help them work out their issues. Usually, it’s some kind of an acute psycho-social crisis. We can help them with that, as well as housing and relationships, and give them a little bit of hope. They move from being acutely suicidal to being less suicidal fairly rapidly. Those are the patients in these units. So I don’t think it’s inevitable that they’re going to kill themselves if they really want to. Patients may want to kill themselves. But we don’t let them. We move them through this period. Maybe it’s a week or two weeks. We get them to a state where they’re feeling much less suicidal.

“Then they leave the unit. Obviously, it’s not a perfect science. We make mistakes. But over the last 10 years, the rate of suicide in our mental health units has dropped dramatically because of all of the environmental changes we’ve made using the checklist.”

--- Mike Richman

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates