Office of Research & Development |

|

About 20 million people worldwide have HIV-associated cognitive disorders. (Illustration: ©iStock/Alexsl)

July 24, 2018

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

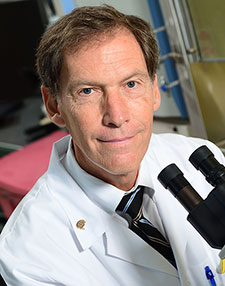

Dr. William Tyor is a neurologist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center who studies the memory problems that affect HIV patients. (Photo by Jack Kearse/Emory)

As people living with HIV age, the effect of the virus on the brain may make them more susceptible than others to developing memory problems from well-known causes like Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury.

So says Dr. William Tyor, a neurologist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center, which treats about 3,000 HIV-infected Veterans. He believes that’s the largest number of any VA facility.

Tyor has long been trying to determine how HIV causes memory problems, in the hope that he and others can develop treatments. He’s learned that interferon alpha (IFNa), a substance the body produces to fight infections, is elevated in the spinal fluid of patients with HIV-linked cognitive disorders, but not in those without.

Most recently, Tyor led a lab study that focused on B18R, a protein made by the smallpox virus that has the ability to tightly bind to IFNa. The researchers found that B18R reversed memory problems in mice with HIV.

The results also suggested that the combination of B18R and standard antiretroviral drugs used by people with HIV—instead of just antiretroviral medication alone—reduced harmful changes in the rodents’ brain tissue. Those changes had included increases in activated glial cells and decreases in nerve cell connections. Both of those patterns can contribute to cognitive dysfunction.

"This study...shows that IFNa affects fundamental aspects of nerve cells trying to form memories."

The study results appeared in the journal AIDS in April 2018.

The B18R and antiretroviral drugs complemented each other in the testing, according to Tyer.

“They acted in concert because they have different actions,” he says. “The antiretroviral therapy inhibits HIV, and the B18R inhibits IFNa. The combination of the two is better than each alone.”

AI to Maximize Treatment for Veterans with Head and Neck Cancer

VA researcher works to improve antibiotic prescribing for Veterans

VA’s Million Veteran Program played crucial role in nation’s response to COVID-19 pandemic

VA Further Develops Its Central Biorepository: VA SHIELD

Tyor says his team is “pioneering” research on B18R, which has never been used in people. But he’s confident the results of his lab studies will offer hope to Veterans and others with HIV-induced cognitive symptoms.

Potential human application of B18R is several years away.

The ability of B18R to improve HIV-linked cognitive disorders in mice is evidence that treatment of IFNa in HIV patients with memory problems could be a viable form of therapy, the researchers write. Investigating pathways whereby IFNa produces adverse effects on brain regions involved in memory may lead to more specific treatments, they note.

The hippocampus is perhaps the best-known brain region involving memory formation.

“We want to know how IFNa messes up nerve cells leading to cognitive dysfunction,” Tyor says. “This study, along with previous publications from my lab, shows that IFNa affects fundamental aspects of nerve cells trying to form memories. Knowing these key disruptions of nerve cell function may not only lead to more specific treatments for HIV cognitive deficits, but may also lead to better treatments for other diseases like Alzheimer’s.”

But the storyline gets a bit more complicated. While B18R seems like good news, Tyor has learned it also poses a side effect of grave concern. The protein’s ability to bind IFNa possibly makes it harder for the body to stop HIV and other viruses from spreading, he says.

“That’s why we’re looking for other downstream targets to block,” says Tyor, who previously served as chief of neurology at the Atlanta VA. “We believe that since there’s redundancy in the interferon system, which includes a series of different types of interferons, blocking only IFNa won’t seriously cripple the interferon system. But the possibility remains that it could leave the body more susceptible to infections. So we have to test its safety in people first.”

He adds: “Viruses have tricky ways of subverting the immune system so they can reproduce themselves more efficiently. One of the ways the smallpox virus does it is by making B18R. This smallpox trick to evade the immune system may prove advantageous as a treatment for high levels of IFNa leading to cognitive dysfunction.”

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a chronic, progressive disease that leads to Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Starting around the time HIV was first identified 30 years ago, Tyor has been trying to determine why about half of the people infected with the virus develop memory problems. That happens, he says, even when those carrying HIV are taking antiretroviral drugs and have suppressed the virus.

VA is the single-largest provider of medical care for patients with HIV/AIDS, treating about 25,000 HIV-infected Veterans. The majority of them are male and non-white.

The Foundation for AIDS Research, amfAR, estimates that 1 million people in the United States and 37 million worldwide are living with HIV. “So you can see this is a big problem since about 20 million people worldwide have HIV-associated cognitive disorders,” says Tyor, who is also a professor at Emory University in Atlanta.

He says HIV cognitive problems include dementia but also milder forms of brain deficits. HIV cognitive deficits are perhaps the most common cause of memory problems in young adults, he says. He and his team have also observed memory deficits in children, who typically contract the virus through maternal transmission.

Tyor’s study involved two lab experiments. In the more important of the two, researchers tested the ability of mice to remember two objects: a plastic container and a light bulb. The researchers found that nine control-group mice not infected with HIV remembered the objects; nine HIV-infected mice that were treated with saline twice daily for seven days didn’t remember them; and nine HIV-infected mice that received B18R twice daily for seven days did remember the container and bulb.

In the other test, scientists looked only at the tissue changes in the rodents’ brains. There were four groups of mice: nine in a control group; nine HIV-infected without any treatment; seven HIV-infected with antiretroviral treatment; and seven HIV-infected with both B18R and antiretroviral therapy.

After 10 days of treatment, the researchers extracted the brains of the mice and analyzed brain sections by microscope for inflammatory signs and nerve cell dysfunction. The results were better in the mice treated with both B18R and antiretroviral medication than in those treated with the medication alone.

Tyor wasn’t surprised by the results of the study. “This has been my theory for almost 30 years,” he says, ”when I discovered IFNa to be elevated in the spinal fluid of HIV patients with cognitive problems. That suggests that IFNa is involved in the development of these cognitive and memory issues.”

He and his team believe the findings support the need for a phase I trial involving HIV-infected people who are experiencing cognitive problems. He hopes to launch a phase 1 trial of B18R by early next year and has been in discussions with the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to fund the study.

He says if B18R is approved by the FDA, it will likely be used by people who are already on antiretroviral medication. “The histopathology test was merely to suggest that B18R will add value to the antiretroviral therapy in humans,” he says.

In addition, B18R will probably be used for treating HIV-associated cognitive disorders, rather than for prevention. “That’s because we’re showing it reverses cognitive problems,” Tyor says. “It would be very expensive to treat everyone when you’re not sure who would get it and who wouldn’t.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates