Office of Research & Development |

|

One brain-stimulation study at the Providence VA is testing the effectiveness of combining transcranial direct current stimulation with virtual reality, a form of prolonged exposure therapy, as a treatment for Veterans with chronic PTSD. In the photo, taken at a VA research exhibit on Capitol Hill in June 2019, a VA staffer tries on a virtual reality headset. (Photo by Robert Williams)

July 10, 2019

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

"There's some reason to think that the frequency of the theta burst stimulation may be better for people who are suffering from PTSD."

A new study found that a form of brain stimulation that can rapidly improve communication between neurons in the brain helped ease PTSD symptoms.

The findings appeared online June 24, 2019, in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

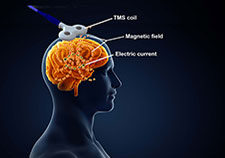

The researchers used theta-burst stimulation, a relatively new form of transcranial magnetic stimulation, on 50 Veterans with chronic PTSD. Theta-burst stimulation can be intermittent or continuous. In this case, the scientists applied it intermittently, or with breaks in the process. Doing so increases the likelihood that the neurons will be more active and will thus communicate with one another, which can potentially reduce PTSD symptoms.

The results showed that intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) “appears to be a promising new treatment for PTSD,” the researchers write. “Most clinical improvements from stimulation occurred [in the first week], which suggests a need for further investigation of optimal iTBS time course and duration.”

Transcranial magnetic stimulation uses a magnetic coil to induce an electrical current in brain cells. (Illustration: iStock/cosmin4000 and Robert Williams)

The researchers stimulated the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in the front part of the brain, in hopes of calming down areas involved in PTSD, such as the hippocampus, which is associated with memory, learning, and emotions. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex helps regulate the amygdala, an area of grey matter that impacts the onset of emotions and is next to the hippocampus. Theta burst stimulation uses rhythms that resemble those in the hippocampus.

“Several factors suggest TBS may be useful in PTSD,” the researchers write. “First, its brevity allows for easy clinical operation and potential combination with psychotherapy. Second, TBS’ patterned nature resembles [theta brain waves in the memory systems of the hippocampus]. PTSD is defined, at its core, by the impact of intrusive traumatic memories. In translational models, TBS can induce activity and the [connection between neurons in the hippocampus]. Taken together, the data provide a theoretical justification for use of TBS for PTSD.”

Dr. Noah Philip, a psychiatrist at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island, led the study. He says this is the first time iTBS has been used on patients with PTSD. He hopes the technology will eventually replace transcranial magnetic stimulation, one of the most widely used forms of brain stimulation. A session with TMS takes about 45 minutes, compared with about 10 minutes for a theta-burst session, meaning iTBS allows for treating more patients in the same block of time, he says.

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

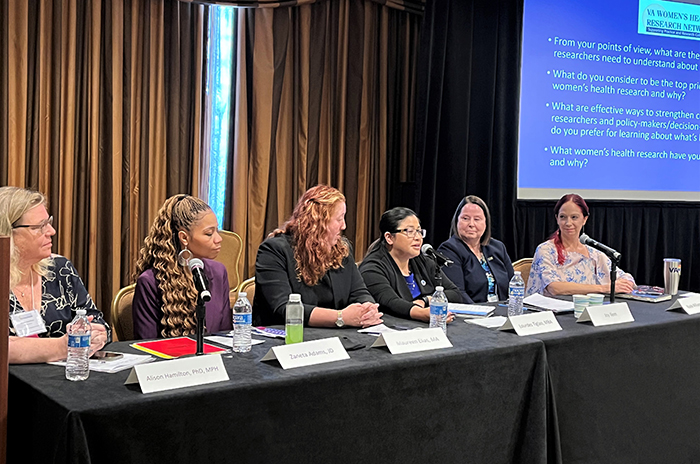

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

Self-harm is underrecognized in Gulf War Veterans

Head trauma, PTSD may increase genetic variant's impact on Alzheimer's risk

Primary Blast Injury of the Brain

A study published last year in the British journal The Lancet showed that a form of iTBS similar to the one used by Philip was just as good as standard transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating depression. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved iTBS for patients with depression that is considered “refractory”—meaning it won’t respond to other treatments—but the technology is only in the testing phase for treating PTSD.

“My interest is in Veterans with PTSD,” says Philip, who is also an associate professor at Brown University in Rhode Island. “The Lancet study took a slightly different approach. But there’s an emerging consensus that these second-generation brain stimulation techniques like theta burst will replace what we currently have.”

Philip runs a transcranial magnetic stimulation clinic at the Providence VA. He’s interested in finding new ways to treat Veterans with PTSD that are safe, that don’t require medication, and that carry minimal side effects. Most of the treatment options used in psychiatry, he says, are medications that have such side effects as diabetes, weight gain, and an impact on sexual function and desire in men and women.

“I’m too familiar with that side effect burden,” he says. “In this case, we used a non-invasive brain stimulation technique that was designed to mimic what’s going in the memory parts of the brain in the hippocampus. There’s some reason to think that the frequency of the theta burst stimulation may be better for people who are suffering from PTSD, which in its essence causes problems related to memory and allows traumatic incidents to influence people on a daily basis. It’s a new and emerging technology that allows us to do more good faster and increase access, and at the same time use our understanding of how the brain is working to design better treatments.”

Understanding the complex nature of PTSD is one of VA’s most pressing challenges. High percentages of Veterans who fought in Vietnam, the Gulf War, and Iraq and Afghanistan have had the mental health condition sometime in their lives.

PTSD symptoms include flashbacks, nightmares, hypervigilance, aggressive behavior, and severe anxiety. People with that condition can also suffer from increased rates of cardiovascular, metabolic, and autoimmune disorders.

In the first phase of Philip’s study, 26 of the 50 participants received a form of magnetic resonance imaging called functional MRI (fMRI) to help the researchers identify signs that would predict who would respond positively to the stimulation. (Only 26 were chosen because some people couldn’t go into an MRI scanner due to shrapnel in their body.) Functional MRI is a common research tool that is not yet used clinically. It can show how a traumatic brain injury, for example, may derail communication between areas of the brain that are normally in sync.

While in the fMRI scanner, the patients were in a resting state. That means they’d lie still and let their mind wander. Even when a person isn’t doing anything, there’s a baseline level of communication between regions in the brain.

Two major themes evolved from the patients who underwent an fMRI, according to Philip.

“The first one is that essentially those people who had what I would call a more normal-looking imaging scan, in other words a healthier-looking network pathology, which is basically how the different brain regions talk to each other, did better in some ways,” he says “Also, with the people in whom the brain regions involved in learning and memory talked to each other more and were more functionally connected, those people also did better.”

“What’s neat is that with this data, we can start thinking about using imaging to test who’s going to respond and who isn’t,” he adds.

Next, the 50 Veterans were randomized evenly into 10 days of sham-based iTBS or real stimulation. Philip and his team were also unaware which treatment the patients received. Plus, the large magnetic coils that were used to administer the short bursts of high-frequency stimulation looked the same, whether they were fake or real, and all participants felt like they were getting some form of stimulation.

At the end of the 10-day period, the researchers learned through clinician assessments and patient reports if the stimulation had eased the symptoms of the 50 participants. The scientists concluded that compared with sham, active iTBS “significantly improved” social and occupational function, which is the ability of people to live normal lives.

The research team also found that reductions in feelings of depression and PTSD symptoms were better with active stimulation than with sham. But improvements in both categories fell short of “significant.”

“People really liked the iTBS,” Philip says. “When they got better, it was a very clear improvement. People would come to the clinic and say, `Hey, I went on a date for the first time in many years’ or `I went out with my wife or was able to go shopping.’ That occurred pretty early on near the two-week mark. Then slowly over the rest of the study we saw other positive signs. That was really nice to see.”

Research has shown that that high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex can help calm down the amygdala. The amygdala and the hippocampus are “sort of intertwined,” Philip notes.

“The way I like to think about it is this is really helping the brain step on the brakes,” he says. “The amygdala is involved in slowing down dangerous memory responses that are involved in PTSD and depression. Essentially, the amygdala lets the brain do what it’s supposed to be doing.”

The researchers then offered another 10 days of unblinded iTBS treatment to all 50 participants, with the results again showing that real stimulation was better than placebo in easing depression and core PTSD symptoms and improving social and occupational function. “We had what we would call statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in most of the things we were looking at,” Philip says. “We also found that real stimulation reduced anger significantly in these Veterans, which we weren’t expecting.”

The side effects from iTBS, Philips notes, were consistent with those of standard transcranial magnetic stimulation. The participants felt a little bit of pain when the procedure started, sort of like a tapping or stinging sensation, and some experienced minor headaches during the stimulation period, he says. He knew of no long-term negative effects from the intermittent theta burst stimulation.

He and his team are now reviewing data to see how the Veterans are faring with their symptoms one year after receiving iTBS treatment.

Currently, Philip and his colleagues are early into two other VA-funded studies that involve brain stimulation. One study is testing the effectiveness of combining transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) with virtual reality, a form of prolonged exposure therapy, as a treatment for Veterans with chronic PTSD. Results from the study may be used to develop a non-medication method for treating those with the mental health disorder.

With tDCS, a small amount of electrical current is applied to the scalp via two or more electrodes—at least one positive and one negative. Positive and negative currents are transmitted to the brain, making brain cells more likely or less likely to be active.

With virtual reality, a person is immersed in a computer-generated virtual environment, either through use of a head-mounted display device or in a room where potentially troubling images are everywhere. The images can help people confront feared situations or locations that may not be safe in real life. The goal is to help reduce their levels of fear and anxiety. Virtual reality includes applications that are meant to simulate battlefield conditions.

The other VA-funded study combines iTBS with a psychotherapy called brief cognitive behavioral therapy (BCBT), in hopes of reducing suicidal thoughts in Veterans who have tried to take their own lives. BCBT is an extension of cognitive behavioral therapy, which is widely used in VA for patients with PTSD. It targets emotions by changing thoughts and behaviors that are contributing to distressing thoughts. BCBT involves four to eight sessions, compared with 12 to 20 for the longer version, and focuses on factors that lead to suicidal thinking.

“I’m excited about combining intermittent theta burst with a psychotherapy to help reduce rates of suicide,” Philip says. “Based on our data, iTBS helped not just with PTSD but with many other things that people are suffering from. We have a tremendous epidemic of suicide right now. That to me seems like where we should apply this. We showed that intermittent theta burst works for a broad range of things. Suicide is the next place to start applying this knowledge.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates