Office of Research & Development |

|

Researchers used MRI scans to identify brain connectivity problems in Veterans with PTSD. (Photo for illustrative purposes only. © Getty Images/TommL)

July 28, 2022

By Tristan Horrom

VA Research Communications

"Understanding executive functioning may help identify more at-risk individuals who experience more long-lasting PTSD and could benefit from personalized treatments aimed toward these cognitive functions and brain circuits."

Veterans with a PTSD subtype characterized by executive function impairments had more chronic PTSD over time and disrupted brain connectivity compared with other forms of PTSD, found a study by VA Boston Healthcare System researchers. Executive functions in the brain give rise to many important skills, like setting and achieving goals, focusing attention on tasks, and juggling multiple tasks at once.

The findings suggest that this pattern of cognitive impairment could contribute to chronic PTSD symptoms. Those with this subtype of PTSD may have unique needs that may not be met with current treatments, according to the researchers. Understanding specific subtypes of PTSD and the biological systems behind them could lead to new targeted treatments for Veterans, they say.

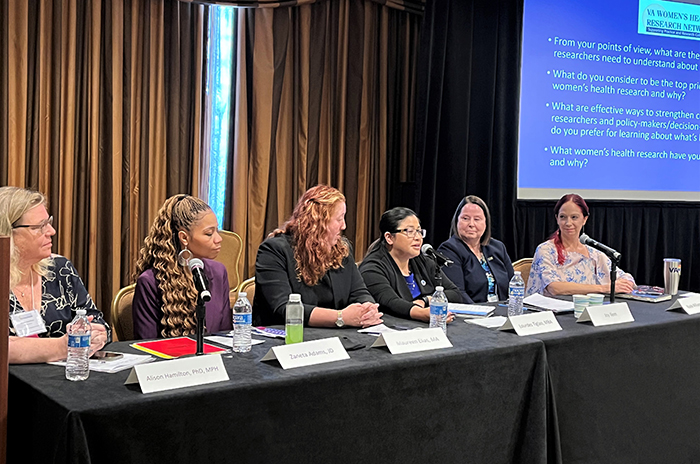

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

Self-harm is underrecognized in Gulf War Veterans

The findings appeared in the June 27, 2022, issue of the journal Translational Psychiatry.

Lead author Dr. Audreyana Jagger-Rickels, a researcher with the VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University, explains that the study could lead to better treatments for PTSD. “These findings suggest that understanding executive functioning may help identify more at-risk individuals who experience more long-lasting PTSD and could benefit from personalized treatments aimed toward these cognitive functions and brain circuits,” says Jagger-Rickels.

Not every person with PTSD experiences the same symptoms, which may be caused by a number of cognitive, emotional, and physical characteristics that differ for each individual. This has led scientists to speculate that many different PTSD subtypes exist, each with its own symptoms and biological underpinnings.

Previous work by the research team at the Boston VA identified a subtype of PTSD characterized by impaired executive functioning. Individuals with this PTSD subtype often have worse memory, attention, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol misuse, compared with people with other subtypes of PTSD.

This research also revealed problems with brain connectivity—how well different parts of the brain communicate with each other.

To better understand how brain connectivity is disrupted in this subtype of PTSD, researchers collected functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans on 368 Veterans, with and without PTSD. They also assessed PTSD symptoms and executive functioning for each Veteran. From the initial group, 175 Veterans underwent a follow-up assessment two years later.

The scans showed that Veterans with an impaired executive function subtype of PTSD had significantly reduced functional connectivity in specific sub-networks of two brain regions: the frontal parietal control network and the limbic network. The frontal parietal network is involved in emotional control, while the limbic network involves learning and memory, as well as social and emotional processing.

This led researchers to conclude that impaired executive functioning in PTSD is tied to a specific pattern of connectivity disruption in these parts of the brain.

The follow-up assessment revealed that patients with PTSD and executive functioning impairment also had more chronic PTSD relative to other types of PTSD, meaning they were more likely to have PTSD symptoms over a longer period of time. The study suggests that chronic PTSD may at least partially be explained by connection disruptions in the brain, say the researchers.

Previous work also identified pre-existing executive dysfunction as a risk factor for developing PTSD. This could mean that connectivity patterns between the frontal parietal control network and limbic network are linked to how susceptible a person is to PTSD, according to the research team.

By better understanding how changes in the brain relate to specific forms of PTSD, the investigators hope to develop symptom-specific treatments. Treatments personalized for this PTSD subtype should consider targeting cognitive training, as well as brain stimulation targeting the specific brain regions affected, they note.

Future areas of research include investigating how targeting executive functioning and underlying brain systems could lead to changes in PTSD symptoms, says Jagger-Rickels. Cognitive training, brain stimulation, or medications could potentially be tailored to specific symptoms. “In the future, Veteran health care may include testing executive functions during PTSD assessment,” she explains. “This could then inform what additional treatment related to executive functioning may be included on top of current evidence-based therapies that treat PTSD.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates