Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

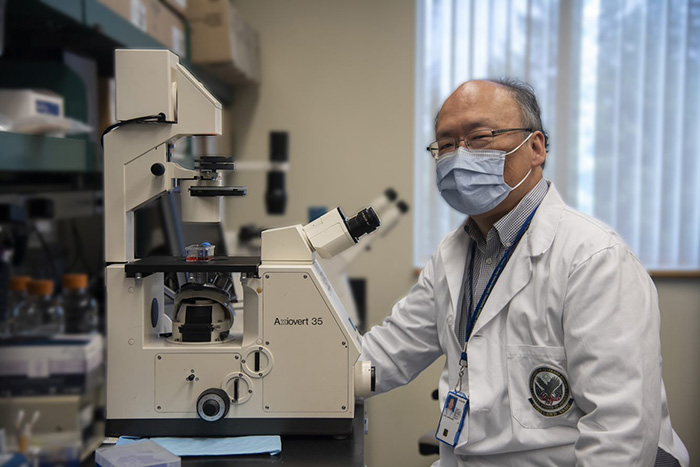

Dr. Shiuh-Wen Luoh led a study using MVP data to validate a new genetic risk model for breast cancer. (Photo by Michael Moody)

August 26, 2021

By Claudia Gutierrez and Tristan Horrom

VA Research Communications

"The goal is to find the right amount of screening that's not too expensive and not too emotionally burdensome, but also effective at detecting breast cancer early in woman with that specific risk. "

A study by VA’s Million Veteran Program showed that a genetic risk model could accurately predict breast cancer in a large group of women Veterans. The tool assesses patients’ DNA for many different genetic variations that, when added together, can elevate a woman’s lifetime risk of breast cancer to 20% or higher, a trigger which usually calls for more actions in current practice.

By scanning a patient’s genome for gene variants using this tool, doctors can create individualized breast cancer screening and risk-reduction plans.

The results appeared in the July 21, 2021, issue of JCO Precision Oncology.

VA researchers using AI to decide best treatment for rectal cancer

VA center training the next generation of researchers in blood clots and inflammation

AI to Maximize Treatment for Veterans with Head and Neck Cancer

Veterans help find new cancer treatments

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer for American women. Although mammogram screenings have lowered the number of deaths from breast cancer, better screening methods could help determine risk and help prevent the cancer before it develops, according to the study researchers.

Previous genome-wide association studies—studies that examine the genes of many people for shared traits related to disease risk—have identified multiple gene variations that appear to increase the risk of breast cancer.

While studies have shown that genetic testing for these variations can help predict breast cancer risk, it is less clear whether they would be as accurate for women Veterans. Veterans experience different environmental exposures and psychological stressors than the general population because of their military service, which may affect disease risk.

By evaluating women Veterans’ individualized genetic risk for breast cancer, specific screening plans could be developed for each patient, according to Dr. Shiuh-Wen Luoh, who led the MVP study. “The goal is to find the right amount of screening that’s not too expensive and not too emotionally burdensome,” explains Luoh, “but also effective at detecting breast cancer early in woman with that specific risk.”

Luoh is a researcher with the VA Portland Health Care System and the Knight Cancer Institute at the Oregon Health & Science University. Dr. Sally G. Haskell of the VA Women Veterans Health Care program and Dr. Cindy Brandt, both with the VA Connecticut Health Care System and Yale University, co-led the research project.

If genetic testing can help determine a woman’s risk for breast cancer, then prevention and screening measures can be tailored to her needs. “Some women may need a mammogram more frequently than every one to two years,” says Luoh. “For others, in addition to mammogram, they may need abbreviated MRI, a shorter form of the scan that studies have shown could be effective and less expensive than a full MRI. Maybe some women may need less frequent screenings and/or don’t need to begin regular mammogram screening until later if their risk is lower.”

To better home in on these specific risk factors, Luoh and colleagues turned to a tool called the Individualized Coherent Absolute Risk Estimator (iCARE). iCARE, developed outside VA, is a computer program that allows researchers to build and evaluate models of risk based on multiple data sources. The models can then be used to estimate an individual’s risk of developing a disease.

The researchers used iCARE and incorporated a model of breast cancer genetic risk based on 313 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. A single-nucleotide polymorphism is one genetic variant at a specific location on the DNA molecule. The variants used in the model have previously been shown to modify breast cancer risk.

Luoh’s team applied the prediction model to the genomes of more than 35,000 women Veterans who had volunteered for MVP. Of those, 338 developed breast cancer during an average follow-up of four years. The screening tool proved to be highly accurate at predicting breast cancer risk, especially in women with European ancestry. Because more data is available on this population than for women of African ancestry or other minority groups, the results cannot be generalized to all populations.

While the study showed that the iCARE assessment was accurate for women Veterans of European ancestry, more work is needed to determine genetic risk factors of breast cancer in non-White Veterans. Most of the research that established the connection between breast cancer and the 313 gene variants was conducted with primarily white participants. It may be that these DNA locations are also involved in breast cancer risk for Black women, says Luoh, but it’s also possible that genes that increase risk are located elsewhere on the genome in Black women.

While more work needs to be done, VA and MVP are in a unique position to find answers. The MVP database includes over 160,000 Veterans of African descent, making it the largest Black cohort in a genetic research program in the world. And according to Luoh, researchers can use data from both men and women to do this research, greatly increasing the data available.

The next step is to apply novel statistical methods and genome-wide association studies specifically focused on Black and other minority Veterans. Luoh and colleagues want to use MVP’s large sample of Black Veterans to see which specific locations are associated with higher breast cancer risk for Black women. This can then be followed by clinical trials to formally evaluate the efficacy of this risk-adapted, personalized breast cancer screening and prevention strategy before translating it into clinics.

MVP is the world’s largest genetic research program of its kind. More than 845,000 Veterans have volunteered for the program. Using its large database of genetic material, along with patient health records, MVP allows researchers to study how genes, lifestyle, and military exposures affect the health and illness of both Veterans and the population at large.

Veterans interested in enrolling in MVP can learn more by visiting mvp.va.gov or calling 866-441-6075.

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates