Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

November 10, 2016

(From left) Drs. Lisa James, Brian Engdahl, and Apostolos Georgopoulos (director) are with the Brain Sciences Center at the Minneapolis VA. They are seen here next to the center's MEG scanner. (Photo by April Eilers)

See also: Voices of VA Research Podcast Series: Biomarkers for Gulf War illness

Listen (5:29), Transcript

Twenty-five years ago, Brian Zimmerman was a strong 6-foot-1 inch, 185-pound Army infantryman in prime physical condition fighting Iraqi forces in Operation Desert Storm.

He witnessed charred Iraqi bodies on the "Highway of Death," including a dead child, took part in a tank battle, and was close to an Iraqi ammunition depot called Khamisiyah that upon detonation is believed to have released nerve agents such as sarin and cyclosarin in the direction of U.S. troops.

Today, Zimmerman, 45, is still entrenched in a battle, but one worlds apart from his military days. He's one of the estimated 300,000 Veterans with Gulf War illness (GWI), which affects various organs, most notably the brain. He experiences symptoms common with that disorder: fatigue, rashes, serious body aches and joint swelling, gastrointestinal problems, memory loss, depression, anxiety, and chronic headaches.

He says his body is deteriorating, and that everyday tasks like getting out of bed can be a struggle.

"We want to be able to provide targeted treatment that's specific to the Veterans' symptoms and genetic risk factors."

"I get joint pain that's astronomical, to the point where there's nothing that makes it go away," says Zimmerman, who also has PTSD. "My hands are getting disfigured from the swelling that goes on. It's like my knuckles are exploding. Three other members from my squad have identical symptoms in their hands. Our hands will just blow up, and your shoulders, your neck, your hips. You get in such extreme pain, there's no getting rid of it. It's almost like you're burning up from the inside."

At the same time, Zimmerman believes there's a "ray of hope" due to the extensive research at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System on Gulf War illness. In one endeavor, scientists there are pursuing the theory that GWI stems from abnormal immune responses that lead to neurological-cognitive-mood (NCM), pain, and fatigue symptoms. The theory prompted their investigation of human leukocyte antigen (HLA). HLA genes are located on chromosome 6 and play key roles in immune system functioning.

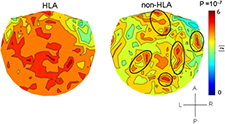

Brain maps based on MEG scan data highlight differences between Veterans with and without Gulf War illness. (Image courtesy of Brain Sciences Center)

Three VA-funded studies led by Dr. Apostolos Georgopoulos, head of the Brain Sciences Center at the Minneapolis VA, identified brain mechanisms and other areas involved in Gulf War illness and found that certain forms, or alleles, of HLA genes offer protection from GWI. A lack of those alleles has made Veterans vulnerable to developing Gulf War illness symptoms. The Minneapolis team further discovered how this protection is manifested in the brain.

The findings could pave the way for immunotherapy for Vets with GWI, or treating symptoms by providing the missing immune protection, says Dr. Brian Engdahl, a psychologist with the Brain Sciences Center who took part in all three studies.

Gulf War Veterans including Zimmerman participated in the studies, published in the past year in EbioMedicine, part of the British Journal Lancet. The first one, which included 66 Vets with GWI and 16 without, found differences in HLA type, based on blood tests, that distinguished these two groups with 84 percent accuracy. Veterans with GWI, in other words, had genetic susceptibility to developing their symptoms.

Brian Zimmerman served with the Army in Operation Desert Storm and recently participated in Gulf War studies at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System. (Photo courtesy of Brian Zimmerman)

In a follow-up study, published in October 2016, the scientists documented sharp differences in brain function between healthy and ill Gulf War Veterans in the cerebellum and frontal cortex.

Forty Vets with GWI and 46 without underwent a magnetoencephalography (MEG) scan, a brain imaging technique that tracks the firing of neurons. It found, with 94 percent accuracy, distinctions between the two groups in synchronous neural interactions, also known as synchrony. Such differences are "excellent predictors of GWI," the researchers write.

Synchrony is important for cognitive functions including attention, memory, and communication between nerves and muscles. Past studies have shown that cognitively healthy people display similar patterns of synchrony, while abnormal synchrony is linked to PTSD and other disorders.

The third study, now in press, combines the HLA risk factors and the brain miscommunication patterns to explain Gulf War symptoms. Sixty-five Gulf War Veterans with GWI and 16 without had MEG scans to assess neural synchrony. The findings show that HLA affects neural synchrony and predicts symptom types, and they indicate that Gulf War illness is caused by the interactions of genetics and exposures.

"Our working hypothesis is that, when exposed to factors such as vaccines, chemical exposures, and stress, genetically vulnerable Veterans exhibit widespread synchronicity anomalies that contribute to diverse problems included under the NCM, pain, and fatigue domains," the researchers write in that study. "Conversely, the presence of protective HLA alleles would prevent these anomalies."

In addition to VA, the University of Minnesota funded the trio of studies, which Engdahl describes as "groundbreaking" research. He says he knows of no other scientists who have used the MEG scan for this purpose, looked at the HLA genotypes of Gulf War Vets, and applied that information to explain what is leading to Gulf War illness symptoms.

He says the research provides a measure of relief to Gulf War Vets like Brian Zimmerman who have been unable to find successful long-term treatments for GWI.

"When you see the results of a brain scan or pull up a blood test result and say, 'All that points to chronic multi-symptom illness,' they say, 'It's real, it's real, it's not just in my head, I haven't been making this up,' Engdahl says. "There's something about objective test results that line up with what you've suffered from that puts the whole picture together. The next question is what can be done about it."

The Minneapolis researchers believe larger cohorts are needed to better validate the findings from all three studies, and they hope the work will lead to clinical treatments.

Engdahl says one of his team's current proposals aims to show that healthy Gulf War Vets have immune responses that work to prevent the brain malfunction seen in ill Gulf War Veterans. The goal then would be to isolate the components that make the difference.

"We're hoping to do that here in the next two years," he says. "We've already demonstrated this in mouse-brain cell cultures."

He says the ultimate objective is giving Vets with Gulf War illness more precise diagnoses and targeted treatments.

"The ideal situation would be in line with the holy grail of modern medicine, especially cancer treatment, where we are able to immunotype you and then provide targeted molecular therapy for your particular set of symptom patterns," Engdahl says. "So it is quite in line with that buzz phrase 'personalized medicine.' We want to be able to provide targeted treatment that's specific to the Veterans' symptoms and genetic risk factors."

Zimmerman, for his part, insists the vaccinations given to troops during the Gulf War as protection from nerve gas and other chemical weapons are behind "a hell of a lot of our problems." A construction worker who lives in Sandstone, Minnesota, he's been to the Minneapolis VA many times over the years to little avail, although he speaks highly of efforts by physicians at that facility to help him and other Gulf War Vets.

He's excited about the research being pursued by Georgopoulos, Engdahl, and their colleagues.

"I'm certain they'll be able to start helping us in a couple of years," Zimmerman says. "I really am."