Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

Dr. John R. Blosnich is a research health scientist with the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion at the VA Pittsburgh Health Care System. (Photo by Bill George)

November 21, 2019

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

Veterans Crisis Line

If you are a Service member or Veteran in crisis or you’re concerned about one, there are specially trained responders ready to help you 24/7. The Veterans Crisis Line connects Service members and Veterans in crisis, as well as their family members and friends, with qualified, caring VA responders through a confidential toll-free hotline, online chat, or text-messaging service. Dial 1-800-273-8255 and Press 1 to talk to someone; send a text message to 838255 to connect with a VA responder; or start a confidential online chat session at VeteransCrisisLine.net/Chat.

A new study finds that social stress factors—such as violence, homelessness, unemployment, marital problems, and a lack of access to care—have strong connections among Veterans to suicidal thinking and suicide attempts.

The findings were presented at an American Public Health Association conference earlier in the month and went online Nov. 19 in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

The researchers linked social stressors to suicidal thoughts and attempts even after adjusting for mental health factors, such as depression, and demographic factors, such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, and marital status. They also suggested that better understanding the social stress history of patients through use of VA’s electronic health record, the Computerized Patient Record System, could improve suicide prevention.

Dr. John Blosnich of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System led the study. He wasn’t surprised social stressors were strongly associated with suicidal ideation, the thought of taking one’s own life, and suicide attempts, even after adjusting for mental health diagnoses. But he was surprised to discover the associations using electronic medical record data, which he says are much different from survey data.

He and his team reviewed data in the VA electronic health record for the period of Oct. 1, 2015, to Sept. 30, 2016. Nearly 300,000 Veterans with at least one inpatient or one outpatient visit at VA sites in VISN (Veterans Integrated Service Network) 4 were included in the study. VISN 4 is a network of more than 50 VA facilities, mostly in mid-Atlantic states.

“In survey data, people tell you directly about what is happening or has happened to them,” says Blosnich, who is also an assistant professor with the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “In electronic medical records, the data about patients come from health care providers. Because health care systems, historically, have not been designed to collect information about social stressors in patients’ lives, we weren’t sure what we would find.”

Doing so proved to be much harder than he first thought.

"Because health care systems, historically, have not been designed to collect information about social stressors in patients' lives, we weren't sure what we would find. "

“To actually understand the extent to which social stressors appear in someone’s medical records, we would need to know from the patient if the stressors are occurring in their lives,” he explains. “We would then compare their self-report to see if the provider put some indication in the medical record about that. In this project, we didn’t have any interaction with patients, so we didn’t know the actual number of social stressors happening with them. We were only getting the story from the medical records.”

Only two social stress factors, Blosnich notes, are picked up through VA clinical screening questions: housing instability and military sexual trauma. Some work is being done on food security–whether a person can access the food he or she needs–and on intimate partner violence, he adds.

“But I don’t know if those clinical screening questions are being used across the whole VA system yet,” he says, “It’s also important to note that for some health care providers, especially VA social workers, these social stressors are front and center every day when they care for Veterans.”

Aside from housing instability and military sexual trauma, the researchers identified the social stressors, such as violence, by finding relevant diagnostic codes in the electronic health record. But the research team had trouble understanding the validity of some of the codes, and it was unclear who included them in the electronic health record. Some providers may also find them hard to comprehend, Blosnich notes. His study gives glimpse of how arcane and confusing the codes may appear to some. For instance:

VA Researcher Named One of U.S.’ Top Female Scientists

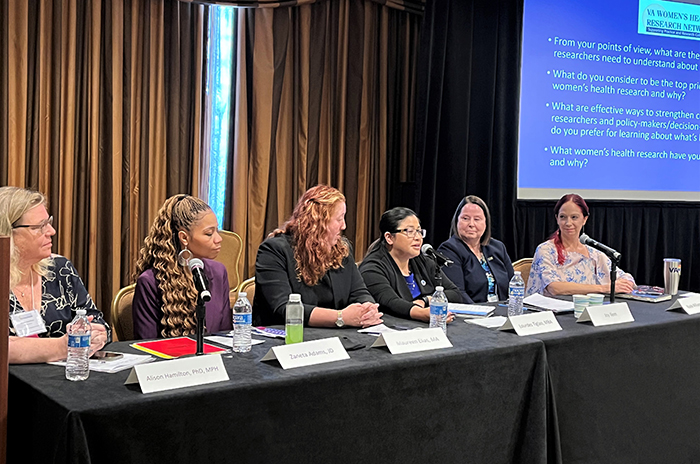

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

Self-harm is underrecognized in Gulf War Veterans

Getting Veterans to explain their social stress problems possibly through clinical screening and incorporating that information in the electronic health record could better help a patient at risk for suicide acquire the necessary care, Blosnich says. The “gold standard” of gathering data is acquiring it first-hand from the patient, he notes. He isn’t sure whether a structured coding system or whether spelling out social stress factors in natural language would be the best way to ensure that a Veteran at risk gets the help he or she needs.

VA is currently transitioning to the Department of Defense’s electronic medical records system, a platform that is commonly called “Cerner,” to allow for seamless care between the agencies.

“For our Veteran patient population, there’s still a lot of stigma about mental health,” Blosnich says. “It’s easy to imagine that a patient may deny being depressed. But if we find out they just lost their job and are worried about losing their house, which in turn is leading to strain with their spouse, we could assume they’re probably having a tough time, and we could implement assistance in ways the Veteran prefers. We can listen for cues on how they want us to try to help. Maybe it includes mental health counseling, but maybe it doesn’t. Maybe it means getting a Veteran connected to a social worker who can help with housing assistance. Maybe it’s getting a Veteran to vocational rehabilitation to get help in finding a job.

“VA has many social workers,” he adds. “We have job rehabilitation, we have housing programs, we have a lot of other services for Veterans to take advantage of. But it’s the process of building bridges to our existing services and then figuring out what new services we might need to develop way down the road, as we figure out more about the comprehensive whole health view of Veterans.”

Blosnich is also a researcher at the VA National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans and an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh. In his work on suicide risk and prevention, he’s mostly interested in non-medical factors instead of medical factors, such as depression or mental illness.

“Mental illnesses are major factors in suicide risk, but they’re not the whole story,” he says. “We’ve known for a long time that social stressors can put people into a period of distress—losing your job, losing your house, ending a relationship, losing a loved one, legal problems. All of those things can contribute to people thinking about killing themselves or trying to kill themselves. Unfortunately, suicide prevention has been focused almost exclusively on mental health treatment, with less attention on the role that social stressors may play in it.”

Suicide prevention is VA’s top clinical priority. The agency says an average of 17 Veterans are dying by suicide every day. VA’s 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report notes that in 2017—the most recent year for which data are available—the suicide rate for Veterans was 1.5 times the rate for non-Veterans, after adjusting for population differences in age and sex.

Blosnich’s study cited seven types of social stress factors: violence, housing instability, financial-employment problems, legal problems, family problems, lack of access to care-transportation, and psychosocial needs. The researchers found that 16.4% of patients had a least one social stress indicator and that each additional one increased odds of suicidal ideation by 67%.

Blosnich and his team were uncertain how to gauge the 16.4% figure because it applied only to Veterans in VISN 4—and because no other study has been published to which the researchers could compare that figure. Given that the figure is based strictly on codes, he’s certain it would be much higher if the electronic health record were designed to capture and reflect a wide range of other social health problems. The investigators found the 67% figure to be “statistically significant,” meaning the strong ties between social stressors and suicidal ideation and attempts were unlikely to be due to chance.

“I wasn’t necessarily surprised [about the 67%] because we know these social factors indicate a Veteran is having a tough time—regardless of whether he or she is managing mental illness,” Blosnich says.

Dr. Peter Gutierrez, a clinical research psychologist at VA Eastern Colorado, says it makes sense that the social stressors highlighted in Blosnich’s study would be associated with suicidal ideation and attempts. At the same time, social stress factors are only one piece of a large puzzle in understanding who’s a suicide risk, he adds.

“There is likely a complex interaction between those and other factors driving their behaviors,” says Gutierrez, who is also co-director of the Military Suicide Research Consortium, a Department of Defense-funded program that researches the causes and prevention of suicide. “The reasons why people die by suicide are complicated and personal. We know broad categories of risk factors, but they combine in different ways for different people. As a result, with current approaches to suicide assessment there’s no good way to predict who will and won’t die by suicide, or to estimate when people known to be at high risk of suicide will act on the thoughts they are having. Studies like this give clinicians contextual factors to consider but not the ability to know who needs what level of treatment or when it’s most needed.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates