Office of Research & Development |

|

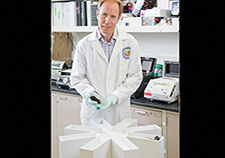

Dr. Prasad Padala demonstrates how repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation works with the help of a staff member at the Little Rock VA. (Photo by Jeff Bowen)

Dr. Prasad Padala demonstrates how repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation works with the help of a staff member at the Little Rock VA. (Photo by Jeff Bowen)

June 26, 2019

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

Patients who display apathy are up to seven times more likely to develop dementia, compared to those without apathy.

The thought of being diagnosed with pre-dementia is unsettling to say the least. The condition, also known as mild cognitive impairment, is marked by memory loss, confusion, mood swings, and other challenges that can disrupt daily life. At least 15% of people with pre-dementia age 65 and older acquire full-blown dementia.

What if someone with pre-dementia also displays apathy? That person is up to seven times more likely to develop dementia, compared to those without apathy, says Dr. Prasad Padala, a geriatric psychiatrist at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression that won't respond to other treatments. The therapy is only in the investigational stages for treating apathy in people with pre-dementia. (Photo by Jeff Bowen)

Apathy, a common problem in patients with pre-dementia, is a profound loss of motivation and initiative. An example would be someone who is reluctant to get out of bed and spends the day sitting around doing nothing.

Padala has been researching apathy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, for about 15 years. Now, he’s leading a study that’s aimed at delaying the onset of Alzheimer’s in people with apathy via a brain stimulation therapy: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). He and his team are hoping that the stimulation will suppress the progression of pre-dementia to dementia by improving apathy.

“Currently, we have more than 5 million Americans with Alzheimer’s and no definitive treatment,” says Padala, who works in the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center at the Central Arkansas VA and also directs the facility’s Memory Disorders Consultation Clinic. “Postponing onset of the disease by even five years will reduce the number of people with Alzheimer’s in half.”

Padala is recruiting 125 Veterans with pre-dementia for his four-year study. They are being randomized to the rTMS group or a sham stimulation. Apathy will be rated according to a scale that measures cognitive, behavioral, and emotional components of motivation. A higher number generally means that someone has apathy, with Veterans needing a score of at least 40 to get into the study.

Can 'young blood' rejuvenate the brain of those with Alzheimer's?

Traumatic brain injuries linked to dementia in older Vets

Experimental drug packs double whammy against Alzheimer's

Former POWs at higher risk for dementia

Apathy can be detected in younger people. But the researchers are recruiting people who are at least 55 years old because of the focus on pre-dementia.

For a therapy, Padala chose rTMS because it’s a non-invasive procedure that has been tested for similar conditions in pilot studies. Plus, he says, it offers the option of targeting a specific area of the brain and adjusting the strength of the simulation for each Veteran.

Clinicians use the technique to target the reward circuitry of the brain, which is strongly linked to motivation and pleasure. Dopamine is released in the reward circuitry to tell someone that he or she has accomplished something good and should do it again.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved rTMS for treating refractory depression, which means patients have been resistant to other forms of therapy. But rTMS is only in the investigational stages for treating apathy in people with pre-dementia.

Using rTMS, Padala will be targeting the pre-frontal cortex of the brain, which houses part of the reward circuitry. Each Veteran will receive 20 sessions of rTMS over four weeks, with 3,000 stimulations each session. The total of 60,000 brain stimulations with a highly focused 3 Tesla magnet—the strength of a standard MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scanner—is key. That stimulation strength was found to be effective in treating refractory depression, according to Padala.

The researchers will pay special attention to how each Veteran responds to the treatment of the first session. At the end of the study, they’ll test if the biomarker and cognition changes after the first session reliably predict the outcomes of the 20 sessions.

“At that point, if we can figure out which Veterans are unlikely to respond to the 20 treatments, it will save a lot of time for those who can be offered some other type of treatment,” says Padala, who is also affiliated with the University of Arkansas.

“At the end of four years, we’ll know for sure if this treatment works for apathy and improves memory or not,” he adds. “But we won’t have enough data to definitely say if this prevents dementia. We’ll have preliminary data, which is what we’ll show when applying for the next grant. We want at least 20 VA sites to be part of a big study.”

This isn’t the first time rTMS has been tested in patients with pre-dementia. But it’s the first study to use rTMS for apathy in patients with pre-dementia, Padala says. He points out that his study will also involve a well-validated sham coil that sets it apart from previous research.

“Sham coiling in TMS studies has always been a problem,” he says. “People used to just tilt the magnet away from the head, so the magnetic field doesn’t penetrate into the brain. But patients can tell if the magnet is facing on their head or outside. Now we use a sham coil that doesn’t have a magnet in it. But it produces the same noise like an MRI machine that makes noise. But the noise is not coming from the coil, even from the real one. The noise is routed through an acoustic blinder, so it comes out from somewhere else. So neither the treater nor the patient can tell if the patient is getting the real coil or the sham coil.”

Knowledge of which coil the patient is getting would bias the results, Padala notes.

In 2013, Padala conducted a pilot study through the University of Arkansas that found that apathy, working memory, and function can be restored using rTMS in some Veterans with pre-dementia. The study included nine people with pre-dementia and apathy, as well as a real rTMS coil and a sham coil. Also, each participant acted as his or her own control and experienced the real and sham treatments at different points. Padala and his colleagues found major improvement in motivation in the patients using the real treatment. The researchers also detected some improvement in their attention span and executive functioning skills, which include managing time, paying attention, and remembering details.

The pilot study helped Padala acquire a $1.1 million VA award to conduct the expanded study.

Padala has also studied a pharmaceutical solution to treat apathy in older Veterans with a mild form of Alzheimer’s. He tested the stimulant methylphenidate (sold under the commercial name Ritalin, among others) in a small group of VA patients. The drug is often used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, a neurological condition that involves difficulty controlling sleep-wake cycles and a poor attention span.

He and his team concluded that Ritalin improved motivation, cognition, functional status, depression, and caregiver burden. But VA patients are generally poor candidates for this medication due to its cardiovascular risks, Padala says.

Currently, Ritalin is being tested at 10 medical sites in the United States and Canada as a treatment for clinically significant apathy in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Padala says the Central Arkansas VA has consistently been the largest recruiting site for the study, which is being funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Padala is one of many VA researchers who are interested in a therapy for patients with Alzheimer’s. He explains that Veterans have a much higher risk of pre-dementia than the general public partly because their rate of diabetes, a chronic disease in which the body can’t produce or properly use insulin, is three times higher. Insulin normally brings sugar out of the bloodstream and into cells. Research has shown that older adults with poorly controlled diabetes are at greater risk for Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

Padala believes that if his ongoing study is successful, it will lead to a new treatment option for apathy in people with pre-dementia.

“Resolution of apathy may improve the functional status of people and their ability to care for themselves, decreasing reliance on caregivers,” he says. “Resolution of apathy will also encourage patients to participate more in their self-care, resulting in improved outcomes of medical conditions. The improved outcomes translate to improved quality of life and reduced costs for caring. Overall, the project has the potential to support Veterans, families, and a society faced with a future associated with Alzheimer’s disease.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates