Office of Research & Development |

|

VA researchers are studying the safety and effectiveness of five types of 3D-printed nasal swabs to be used to test for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. (Photo for illustrative purposes only. ©iStock/Diy13)

July 12, 2021

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

"Our focus for the study is COVID-19. But if these 3D-printed swabs show the ability to collect and release viral matter for clinical testing, then they may be suitable for many use cases, including the detection of common viruses.”

In August 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration reported shortages in the national supply of nasal swabs used to test for the virus, among other supplies such as personal protective equipment.

While VA went on to secure an adequate supply of swabs, the FDA cited a larger national shortage as recently as March of this year.

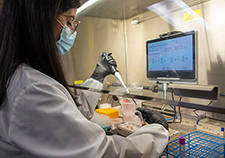

Although the pandemic has receded and many Americans have been vaccinated, VA isn’t taking any chances. VA researchers are studying the safety and effectiveness of 3D-printed nasal swabs, in case of another urgent nationwide need to test patients for COVID-19 or other infectious diseases. The agency is hoping to offset further potential shortages of traditional swabs in the commercial supply chain and aims to provide scientific evidence of the value of 3D swabs to the non-VA health care system, as part of VA’s mission to support national health care during the pandemic.

Dr. Joseph Iaquinto, a biomedical engineer in the VA Center for Limb Loss and Mobility at VA Puget Sound in Washington state, is leading the study. His team is aiming to examine the viability of five types of 3D swabs, two of which have been produced by VA and the rest by commercial 3D printing companies. Iaquinto believes 3D swabs were not on the commercial market before the pandemic.

Part of the “elegance” of the study, Iaquinto says, is that the researchers are using a swab cartridge that can simultaneously test for a battery of viruses. There are six viral targets, including the novel coronavirus, Flu A, Flu B, and the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the most important cause of lower respiratory tract infection in young children.

“Our focus for the study is COVID-19,” Iaquinto says. “But if these 3D-printed swabs show the ability to collect and release viral matter for clinical testing, then they may be suitable for many use cases, including the detection of common viruses.”

Since the start of the pandemic, VA innovators, researchers, and clinicians have helped build a more resilient supply chain of personal protective equipment and other supplies to support VA’s response to the health crisis. These items have included face masks, face shields, hoods, desk shields, and nasal testing swabs. In many cases, 3D printing has been involved due to its flexibility in producing new products.

The benefit of 3D printing is the ability to “radically change your digital design or to design something entirely different, then quickly print it into the real world,” Iaquinto explains. “That allows you to prototype or flex production with higher speed than other pathways.”

In the nasal swab study, researchers intend to provide statistical evidence on the safety and effectiveness of 3D swabs in use and nearing readiness for use. The goal is to identify which 3D swab designs, if any, provide the same clinical result as traditional swabs.

AI to Maximize Treatment for Veterans with Head and Neck Cancer

VA researcher works to improve antibiotic prescribing for Veterans

VA’s Million Veteran Program played crucial role in nation’s response to COVID-19 pandemic

VA Further Develops Its Central Biorepository: VA SHIELD

The study calls for swabbing Veterans and VA employees for COVID-19 testing who show up as a matter of routine care. But the researchers are amending the study to recruit patients who are in the hospital, have contracted COVID-19, or are symptomatic, but are not scheduled for swabbing.

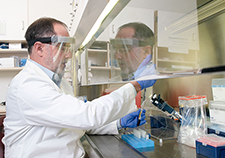

Participants are first swabbed with a traditional swab, then with another traditional swab or a 3D swab.

“In a more ideal clinical study, you would randomize which swab is done first,” says Iaquinto, who is also an assistant professor at the University of Washington. “However, since double swabbing is not clinically validated, we didn’t want the study to interfere with the Veterans’ ability to get the best clinical result. So to accommodate that, we set it so they always get their clinical swab first and the research swab second.”

However, he adds, this raises a new question: “What if the order in which you swab alters the result? Guidance from our clinical collaborators suggested several scenarios. It could be that you remove most of the viral matter on the first swab. So by the time you do the second swab, you’re always going to have less material. Or it could be the other way around. You could loosen up nasal material on the first swab, and on the second swab you get more viral material. Either of those is a bias from a scientific standpoint. Therefore, we randomize the second swab to determine if there is an ordering bias.”

In a noninferiority trial, the ability of the 3D swabs to detect coronavirus is compared to that of the traditional swab. That means the study is designed not to show that treatments are equal, or not different, but that the new treatment is not unacceptably worse than, or non-inferior to, an active control. When the researchers are confident a 3D swab is not inferior, they will begin evaluating the next swab design.

“We are comparing the 3D swab result to the traditional swab result, not the unknown true disease of the participant,” Iaquinto says. “It is known that the traditional swabs and even [COVID-19] testing are not 100% accurate. Therefore, we don’t have a ground truth to compare to. Essentially, we are trying to confirm that if we use a 3D swab, we are confident that it would give the same result we would have gotten if we used a traditional swab.

“Alongside this is an eye toward the safety of these swabs,” he adds. “We are closely monitoring the differences in nosebleed rates, for example, when using traditional or novel swabs.”

This study has two phases. In the first phase, the researchers evaluate 3D swab performance in 30 COVID-19 positive and 30 COVID-19 negative participants. For swabs that are shown immediately to be inferior, the research team will continue to evaluate them in the second phase by performing interim analyses on every 50 participants.

“Swabs that are inferior will be identified very quickly, allowing us to pivot to the next potential design,” Iaquinto says. “This approach respects the time invested by Veteran participants and preserves study resources.”

Four VA medical centers are participating as recruiting sites: Long Beach, California; Charleston, South Carolina; Orlando, Florida; and Cleveland. VA Puget Sound is the coordinating site. Ninety-five Veterans have enrolled to date.

“The investigators and staff teams at those sites have worked very hard and very quickly to make this study possible,” Iaquinto says. “I want to recognize their `boots on the ground’ effort to recruit participants and manage their study duties. I’m very honored to have them as teammates.”

The five swabs selected for the study come from FDA-registered production facilities. In an initial evaluation, VA tested their design as part of COVID TRUST, a memorandum of understanding among VA, NIH, and FDA. Those tests were meant to demonstrate benchtop safety and effectiveness. They are available on the NIH 3D Print Exchange, which provides models in formats that are compatible with 3D printers, and are explained on FDA’s information page on 3D printing medical devices.

Two of the 3D swabs under evaluation were designed by commercial entities but were made by VA, in accordance with FDA criteria. A team led by biomedical engineer Nicole Beitenman at the Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center in Charleston, South Carolina produced one of the swabs. A team led by biomedical engineer Arrianna Willis at VA Puget Sound is making another swab. The other three swabs are commercially available.

The VA Innovation Ecosystem and the VA Office of Research and Development are collaborating to support the study. VA Ventures, which was formed last year in partnership with the Innovation Ecosystem, is one of the VA programs that has designed, fabricated, and evaluated equipment for VA’s COVID-19 response. Iaquinto is also affiliated with VA Ventures, which is managing the swab production facility at VA Puget Sound.

“This study is a great example of how multiple services at VA—the Innovation Ecocystem, the Office of Research and Development, the National Program Office for Sterile Processing, Procurement and Logistics, and the Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Service—are working together to support VA’s continuity of care for its Veterans and employees,” Iaquinto says. “It’s collaboration at its best.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates